Contents

Highlighting indicates debut books

Discussions are open to all members to read and post. Click to view the books currently being discussed.

Literary Fiction

Historical Fiction

Short Stories

Essays

Poetry & Novels in Verse

Mysteries

Thrillers

Romance

Fantasy, Sci-Fi, Speculative, Alt. History

Biography/Memoir

History, Current Affairs and Religion

Science, Health and the Environment

Literary Fiction

Historical Fiction

Poetry & Novels in Verse

Thrillers

Romance

Fantasy, Sci-Fi, Speculative, Alt. History

Biography/Memoir

| BookBrowse: | |

| Critics: |

An exhilarating debut from a radiant new voice, After Sappho reimagines the intertwined lives of feminists at the turn of the twentieth century.

"The first thing we did was change our names. We were going to be Sappho," so begins this intrepid debut novel, centuries after the Greek poet penned her lyric verse. Ignited by the same muse, a myriad of women break from their small, predetermined lives for seemingly disparate paths: in 1892, Rina Faccio trades her needlepoint for a pen; in 1902, Romaine Brooks sails for Capri with nothing but her clotted paintbrushes; and in 1923, Virginia Woolf writes: "I want to make life fuller and fuller." Writing in cascading vignettes, Selby Wynn Schwartz spins an invigorating tale of women whose narratives converge and splinter as they forge queer identities and claim the right to their own lives. A luminous meditation on creativity, education, and identity, After Sappho announces a writer as ingenious as the trailblazers of our past.

After Sappho, by Selby Wynn Schwartz

The problems of Albertine are

(from the narrator's point of view)

a) lying

b) lesbianism,

and (from Albertine's point of view)

a) being imprisoned in the narrator's house.

—Anne Carson, The Albertine Workout

Sappho, c. 630 BCE

The first thing we did was change our names. We were going to be Sappho.

Who was Sappho? No one knew, but she had an island. She was garlanded with girls. She could sit down to dine and look straight at the woman she loved, however unhappily. When she sang, everyone said, it was like evening on a riverbank, sinking down into the moss with the sky pouring over you. All of her poems were songs.

We read Sappho at school, in classes intended merely to teach poetic meter. Very few of our teachers imagined that they were swelling our veins with cassia and myrrh. In dry voices they went on about the aorist tense, while inside ourselves we felt the leaves of trees shivering in the light, everything dappled, everything trembling.

We were so young then that we had never met. In back gardens we read as much as we could, staining our dresses with mud and pine-pitch. Some of us were sent by our families to distant schools to be finished, so that we would come to our proper end. But it was not our end. It was barely our beginning. Each one lingered in her own place, searching the fragments of poems for words to say what it was, this feeling that Sappho calls aithussomenon, the way that leaves move when nothing touches them but the afternoon light.

At that time we were not called anything and so we cherished every word, no matter how many centuries dead. Reading of the nocturnal rites of the pannuchides we stayed up all night; the exile of Sappho to Sicily turned our eyes to the sea. We began writing odes to clover blossoms and blushing apples, or painting on canvases that we turned to the wall at the slightest sound of footsteps. A sidelong glance, a half-smile, a hand that rested on our arms just above the elbow: we had not yet memorized the lines for these occasions. Or there were only fragments of lines that we could have offered, in any case. Of the nine books of poems written by Sappho, mere shreds of dactyls survive, as in Fragment 24C: we live/…the opposite/…daring.

CHAPTER ONE

Cordula Poletti, b. 1885

Cordula Poletti was born into a line of sisters who didn't understand her. From the earliest days, she was drawn toward the outer reaches of the house: the attic, the balcony, the back window touched by the branches of a pine tree. At her christening she kicked free of the blankets bundled around her and crawled down the nave. It was impossible to swaddle Cordula long enough to name her.

Cordula Poletti, c. 1896

Whenever she could, she took a Latin primer from the Biblioteca Classense and went to sit in a tree near the cemetery. In her house they called, Cordula, Cordula!, and no one would answer. Finding Cordula's skirts discarded on the floor, her mother openly despaired of her prospects. What right-minded citizen of Ravenna would marry a girl who climbed up the trees in her underthings? Her mother called, Cordula, Cordula?, but there was no one in the house who would answer that question.

X, 1883

Two years before the christening of Cordula, Guglielmo Cantarano published his study of X, a twenty-three-year-old Italian. In excellent health, X went whistling through the streets and kept a string of girlfriends happy. Even Cantarano, who disapproved, had to admit that X was jovial and generous. X would throw a shoulder to a wheel without complaint, could make a room roar with laughter. It wasn't that. It was what X was not. X was not a willing housewife. X remained unmoved by squalling infants, would not wear skirts that swaddled the stride, had no desire to be pursued by the hot breath of young men, failed to enjoy domestic chores, and possessed none of the decorous modesty of maidenhood. Whatever X was, Cantarano wrote, it was to be avoided at...

Excerpted from After Sappho by Selby Wynn Schwartz. Copyright © 2023 by Selby Wynn Schwartz. Excerpted by permission of Liveright/W.W. Norton. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

"Someone will remember us, I say, even in another time."

—Sappho, fragment 147

"Who was Sappho?" asks Selby Wynn Schwartz in the prologue to After Sappho. An ancient Greek lyric poet whose work survives only in fragments, most of Sappho's life has been the subject of fanciful speculation. We know she was from Lesbos; we know she was exiled to Sicily; we know that she had an island and was, as the prologue says, "garlanded with girls." Much of her work has been lost, but Sappho herself survives in collective memory as an extraordinary woman and artist who blazed her own trail and became legend.

For the women in this novel, and for the narrators who chronicle and comment upon the unfolding events like a Greek chorus, Sappho is the flame that kindles their creativity, the beacon that guides them, igniting their love and passion, turning their eyes toward the sea, and lighting the way into new, uncharted waters. The "we" used by the chorus of narrators becomes the "we" of all women who break new ground, transgress societal boundaries, love other women, and emulate Sappho by leaving lasting artistic legacies of their own.

In her debut novel, Schwartz presents a lavish, vibrant, kaleidoscopic re-imagining of the lives of early twentieth-century Sapphic feminists. With a narrative structure echoing the fragmentation of Sappho's surviving poems, their stories are set against a world that was changing rapidly but remained intransigent when it came to women's rights. The novel initially focuses on two Italian feminist writers: Sibilla Aleramo and Lina Poletti. Through their stories, readers witness the slow, painful process of recognizing women's legal equality. The narrative follows Aleramo as she is given in marriage to her rapist at only sixteen, an action that is legally sanctioned, later leaving her abusive husband and losing the right to see her child. The book is peppered throughout with information on feminists' legal and political battles, contextualizing obstacles women faced when attempting to lead their own lives and follow in Sappho's footsteps.

The primary focus, however, is on the women themselves, as the story moves from Italy across Sappho's Mediterranean to encompass other key female figures in the art, literature, and politics of the time. These include Ukrainian-Italian activist Anna Kuliscioff, American writer and literary salon hostess Natalie Barney, English poet Radclyffe Hall, American painter Romaine Brooks, actresses Eleonora Duse and Sarah Bernhardt, dancers Isadora Duncan and Ida Rubenstein, and writers Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West. This dazzling array of women free themselves from their constraints and establish their own artistic communities. Blending history and fiction in a lush, sensual style reminiscent of lyric poetry, the novel follows each woman carving out a new life for herself and taking up Sappho's legacy to create art and blaze trails for future generations.

After Sappho often moves among these women's stories in nonlinear style, piecing together a patchwork pattern of intertwined lives and relationships. With such a wide scope, the novel's episodic nature occasionally seems almost too fragmented and even hurried; at times, readers might wish they could stay a bit longer with each woman and explore her life in more depth.

Nonetheless, Sappho's work permeates the stories with incisive and relevant excerpts from her poems, creating evocative snapshots of lives that jointly contributed to a flowering of female creativity. Toward the latter part of the book, in contrast to Sappho's idealism, the prophetess Cassandra becomes more prominent. With war and fascism on the horizon, her ominous portents highlight the fragile foundation upon which women's rights rested a century ago and can also be seen as foreshadowing the world today. In an era in which feminism's gains appear to be on shaky ground, this book reminds us of women's interconnectedness across generations, and how those who came before can inspire us to keep going, keep fighting, and keep creating.

Reviewed by Jo-Anne Blanco

Lucy Ellmann, author of Ducks, Newburyport

Lucy Ellmann, author of Ducks, Newburyport

Selby Wynn Schwartz's debut novel After Sappho reimagines the lives of early 20th century lesbian authors and artists. The novel tells the story of how these women ignited a radical feminist movement inspired by the ancient Greek poet Sappho, broke free from conventions to pursue their own desires and creativity, and flourished within their own women-only communities. In her 1907 work Comment les femmes deviennent écrivains (How Women Become Writers), the French writer Aurel, who ran her own literary salon from 1915 until her death in 1948, stated her belief that women should not follow the rules for writing that had been laid down by men. "It was time for women to take language for themselves, Aurel said, even one word at a time, to take their own names and become. To become one word."

Selby Wynn Schwartz's debut novel After Sappho reimagines the lives of early 20th century lesbian authors and artists. The novel tells the story of how these women ignited a radical feminist movement inspired by the ancient Greek poet Sappho, broke free from conventions to pursue their own desires and creativity, and flourished within their own women-only communities. In her 1907 work Comment les femmes deviennent écrivains (How Women Become Writers), the French writer Aurel, who ran her own literary salon from 1915 until her death in 1948, stated her belief that women should not follow the rules for writing that had been laid down by men. "It was time for women to take language for themselves, Aurel said, even one word at a time, to take their own names and become. To become one word."

The emergence of a new kind of literature written by women in this period did not go unnoticed and was often received with hostility. In 1905, the English writer Virginia Woolf published a review refuting the conclusions of W. L. Courtney's The Feminine Note in Fiction, in which Courtney claimed, among other things, that women's attention to detail precluded them from becoming artists and that, by writing books for other women, women authors placed the art of the novel in jeopardy. To counter these assertions, Woolf presented Sappho and Jane Austen as evidence that women could combine what Courtney called their passion for "exquisite detail" with supreme artistry. Woolf also pointed out that women had only recently won access to education and the study of Latin and Greek classics and, given time, women would "fashion it [their literature] into permanent artistic shape."

By 1905, this revolutionary reshaping of literature by women was already under way. A central figure of this new movement and a key character in After Sappho is the American writer Natalie Barney, whose work and life was inspired by Sappho. As one of the first modern women to write openly lesbian poetry, in 1901 Barney (under the pseudonym Tryphé) published Cinq Petits Dialogues Grecs (Five Short Greek Dialogues) about her lover Renée Vivien, herself the first lesbian translator of Sappho's poetry. Vivien wrote the poem The Death of Sappho shortly before her own untimely death in 1909. The French writer Colette, another of Barney's lovers, recounted Vivien's story in her acclaimed 1932 novel The Pure and the Impure.

Many other figures in After Sappho are connected through their association with Barney. The dancer and courtesan Liane de Pougy recounted their romance in her 1901 novel Idylle Saphique, while English author Radclyffe Hall gave a celebrated reading of her 1928 novel The Well of Loneliness at Barney's salon, not long after the book had been banned in the UK for its depiction of lesbianism. At the same time, in England, after her scathing response to Courtney, Virginia Woolf had embarked upon a relationship with the writer Vita Sackville-West, a romance that led to the writing of her 1928 novel Orlando: A Biography. The novel's protagonist, based on Sackville-West, lives for more than 400 years and metamorphoses from a man into a woman, implying that love transcends all boundaries of sex and convention.

As the 1920s drew to a close, Aurel's hopes that women writers would discard the old rules and take on their own language were being fulfilled. This new kind of literature built a foundation for the extraordinary wealth of women's literature we enjoy today.

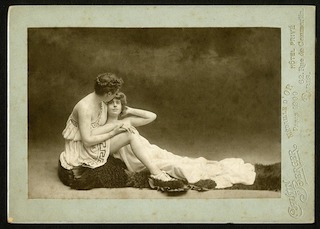

Natalie Barney and Colette, c. 1906, photo by Cautin and Berger, Paris, from Smithsonian Institution, Alice Pike Barney Papers

Filed under People, Eras & Events

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.