Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' Opinion:

First Published:

Oct 2008, 432 pages

Paperback:

Aug 2009, 448 pages

Book Reviewed by:

Book Reviewed by:

Karen Rigby

Buy This Book

An eye-opening and previously untold story, Factory Girls is the first look into the everyday lives of the migrant factory population in China.

China has 130 million migrant workers—the largest migration in human history. In Factory Girls, Leslie T. Chang, a former correspondent for the Wall Street Journal in Beijing, tells the story of these workers primarily through the lives of two young women, whom she follows over the course of three years as they attempt to rise from the assembly lines of Dongguan, an industrial city in China’s Pearl River Delta.

As she tracks their lives, Chang paints a never-before-seen picture of migrant life—a world where nearly everyone is under thirty; where you can lose your boyfriend and your friends with the loss of a mobile phone; where a few computer or English lessons can catapult you into a completely different social class. Chang takes us inside a sneaker factory so large that it has its own hospital, movie theater, and fire department; to posh karaoke bars that are fronts for prostitution; to makeshift English classes where students shave their heads in monklike devotion and sit day after day in front of machines watching English words flash by; and back to a farming village for the Chinese New Year, revealing the poverty and idleness of rural life that drive young girls to leave home in the first place. Throughout this riveting portrait, Chang also interweaves the story of her own family’s migrations, within China and to the West, providing historical and personal frames of reference for her investigation.

A book of global significance that provides new insight into China, Factory Girls demonstrates how the mass movement from rural villages to cities is remaking individual lives and transforming Chinese society, much as immigration to America’s shores remade our own country a century ago.

1

Going Out

When you met a girl from another factory, you quickly took her measure. What

year are you? you asked each other, as if speaking not of human beings but of

the makes of cars. How much a month? Including room and board? How much for

overtime? Then you might ask what province she was from. You never asked her

name.

To have a true friend inside the factory was not easy. Girls slept twelve to a

room, and in the tight confines of the dorm it was better to keep your secrets.

Some girls joined the factory with borrowed ID cards and never told anyone their

real names. Some spoke only to those from their home provinces, but that had

risks: Gossip traveled quickly from factory to village, and when you went home

every auntie and granny would know how much you made and how much you saved and

whether you went out with boys.

When you did make a friend, you did everything for her. If a friend quit her job

and had nowhere to stay, you shared your bunk ...

Factory Girls does not propose solutions, nor is it meant as a comprehensive guide to current trends in the industry. Instead the author leaves it up to the reader to draw his or her own moral conclusions. Although some readers may notice an absence of the more salient controversies (from the USA point of view) surrounding the factories, such as extensive discussions on unionization or the lack thereof, livable wages, or whether or not foreign corporations should be outsourcing their manufacturing processes in the first place, the author appears to be focusing more on the human-interest perspective, and as such, succeeds wonderfully when it comes to following Chunming, one of the main subjects, whose journey rivals that of any fictional protagonist. One of the highlights occurs when Chang visits Chunming's family. Growing up in a communal village where privacy is nominal goes a long way towards explaining the initial loneliness the girls experience in an anonymous city like Dongguan, but also the freedom most of them come to appreciate, even when it comes at a high cost...continued

Full Review

(758 words)

This review is available to non-members for a limited time. For full access,

become a member today.

(Reviewed by Karen Rigby).

Lisa See

Often people ask me, 'What's it like for women in China today?' From now on I'll recommend Leslie T. Chang's Factory Girls, which is brilliant, thoughtful, and insightful. This book is also for anyone who's ever wondered how their sneakers, Christmas ornaments, toys, designer clothes, or computers are made. The stories of these factory girls are not only mesmerizing, tragic, and inspiring—true examples of persistence, endurance, and loneliness—but Chang has also woven in her own family's history, shuttling north and south through China to examine this complicated country's past, present, and future.

Lisa See

Often people ask me, 'What's it like for women in China today?' From now on I'll recommend Leslie T. Chang's Factory Girls, which is brilliant, thoughtful, and insightful. This book is also for anyone who's ever wondered how their sneakers, Christmas ornaments, toys, designer clothes, or computers are made. The stories of these factory girls are not only mesmerizing, tragic, and inspiring—true examples of persistence, endurance, and loneliness—but Chang has also woven in her own family's history, shuttling north and south through China to examine this complicated country's past, present, and future. Simon Winchester

Rising head and shoulders above almost all other new books about China, this unflinching and yearningly compassionate portrait of the lives and loves of ordinary Chinese workers is quite unforgettable: it presents the first long, hard look we have ever taken at the people who are due to become, before very much longer, the new masters of the world.

Simon Winchester

Rising head and shoulders above almost all other new books about China, this unflinching and yearningly compassionate portrait of the lives and loves of ordinary Chinese workers is quite unforgettable: it presents the first long, hard look we have ever taken at the people who are due to become, before very much longer, the new masters of the world.Factory Girls is an example of immersion journalism. Immersion

journalism involves more depth than traditional newspaper reporting, which is

limited by column space and time, and includes less of the reporter's own

thoughts and reactions to events. Classic examples include Truman Capote's

In Cold Blood (1966), Joan Didion's Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968), and

George Orwell's Homage to Catalonia (1952). More recent examples include

Nickel & Dimed and

Self-Made Man.

The style is related to but different from New Journalism, which developed in the 1960s and 70s and

was first described by Tom Wolfe. New Journalism, which tends to be found

in magazines, not newspapers, uses dialogue, the first-person point of view,

...

This "beyond the book" feature is available to non-members for a limited time. Join today for full access.

If you liked Factory Girls, try these:

by Amelia Pang

Published 2022

In 2012, an Oregon mother named Julie Keith opened up a package of Halloween decorations. The cheap foam headstones had been $5 at Kmart, too good a deal to pass up. But when she opened the box, something fell out that she wasn't expecting: an SOS letter, handwritten in broken English by the prisoner who'd made and packaged the items.

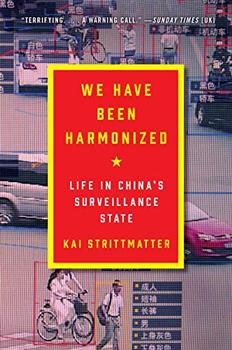

by Kai Strittmatter

Published 2021

Hailed as a masterwork of reporting and analysis, and based on decades of research within China, We Have Been Harmonized, by award-winning correspondent Kai Strittmatter, offers a groundbreaking look at how the internet and high tech have allowed China to create the largest and most effective surveillance state in history.

The House on Biscayne Bay

by Chanel Cleeton

As death stalks a gothic mansion in Miami, the lives of two women intertwine as the past and present collide.

The Flower Sisters

by Michelle Collins Anderson

From the new Fannie Flagg of the Ozarks, a richly-woven story of family, forgiveness, and reinvention.

The Funeral Cryer by Wenyan Lu

Debut novelist Wenyan Lu brings us this witty yet profound story about one woman's midlife reawakening in contemporary rural China.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.