Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' Opinion:

First Published:

Mar 2023, 336 pages

Paperback:

Mar 2024, 336 pages

Book Reviewed by:

Book Reviewed by:

Kim Kovacs

Buy This Book

At eighteen Rose was employed on the sweet counter at Woolworths, and one evening met Jim at a dance in Camberwell. Jim took to Rose from the minute they began talking. She was a down-to-earth girl, with no side to her. She wasn't mouthy—not like some when a soldier chatted them up—and she wasn't a wallflower either. Solid, that was Rose, an honest sort, and it didn't take long for Jim to love her for it. In fact, Jim adored his Rose. He was with the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers—REME—where his ability to remain calm under pressure led to training in bomb disposal before being stationed in London, where his skills were needed most. Experience had taught him how to keep breathing and retain a steady hand while executing the precise movements required to remove the detonator from one of those great big UXBs—unexploded bombs. He explained to Rose that the Germans deliberately made a lot of bombs so they didn't explode when they landed, because they knew the strain of having a UXB in the street, its menacing tail fins sticking out of the tarmac, would cause the British people to get nervy. It was all to undermine morale. Rose remembered those words when she met Jim's family. It seemed to her that Jim's dad was like that, and so were his brothers; they had dodgy detonators that scared the you-know-what out of people and undermined their morale.

Jim's family, all still very much alive, lived south of the river in Walworth. John Mackie—Jim's dad—was angry when Jim told the family he and Rose were planning to move to the country. He told them Jim was mad to leave the manor —that's what he called it, his "manor," as if he owned the streets, which really, Rose supposed he did. The old man disowned Jim after the young couple added that they were going anyway because they wanted to bring up Susie in fresh country air, away from bomb sites. John Mackie got up from the table, took an ornate china bowl and ewer from a marble-topped sideboard, poured water from the ewer into the bowl and began scrubbing his hands. He made a show of shaking out the water and taking a towel to dry himself. "I wash my hands of you—but you will be back. You wait and see. Even if you leave her and the girl behind, you will be back. You belong in this family, Jim Mackie, and don't ever think otherwise—you're nothing, nothing at all without us, and let's see the look on your yellow face when you come crawling home."

"That was horrible," said Rose later.

"We both know what he's like," said Jim. "He's a hotheaded, miserable old sod."

In those early weeks, every day without word from the Mackie family was a relief, and now Rose had begun to believe she would never see them again. As far as she and Jim were concerned, his people could languish away in his father's so-called manor for a long time. They'd had enough of their London lives to last them all the way to the other side, wherever it was. To be fair, Jim's mum had cried when they walked away, but she was no angel either.

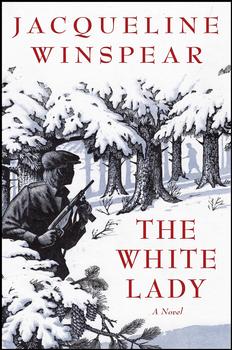

Rose popped Susie into her pushchair, tucked a blanket around her chubby little legs, handed her Teddy One Eye and locked the door, pressing hard against it to make sure the lock held. It was always important to make sure. She stopped for a moment as she maneuvered the pushchair along the path, turning to glance back at the dwelling. It wouldn't have been much to most; a sixteenth-century weatherboard cottage with only cold running water—and yes, it could do with a drop of paint, some new flashing around the base of the chimney, and that outside toilet was bitterly cold in winter—but it had become her beloved home. She tucked a strand of coppery hair behind her ear, smiled and said aloud, "Thank you, my lovely house." Then she went on her way, wondering if she'd see the quiet woman this morning, the one who walked along the road every single day. That's what they called her in the village—"the quiet woman"—and Rose could understand why, though she was also known as "the White lady" on account of her surname and the fact that she seemed like, well, a lady.

Excerpted from The White Lady by Jacqueline Winspear. Copyright © 2023 by Jacqueline Winspear. Excerpted by permission of Harper. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The House on Biscayne Bay

by Chanel Cleeton

As death stalks a gothic mansion in Miami, the lives of two women intertwine as the past and present collide.

The Flower Sisters

by Michelle Collins Anderson

From the new Fannie Flagg of the Ozarks, a richly-woven story of family, forgiveness, and reinvention.

The Funeral Cryer by Wenyan Lu

Debut novelist Wenyan Lu brings us this witty yet profound story about one woman's midlife reawakening in contemporary rural China.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.