Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' Opinion:

First Published:

Jan 2014, 416 pages

Paperback:

Feb 2015, 416 pages

Book Reviewed by:

Book Reviewed by:

Elena Spagnolie

Buy This Book

Excerpt

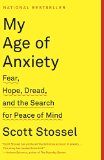

My Age of Anxiety

Some eighty years ago, Freud proposed that anxiety was "a riddle whose solution would be bound to throw a flood of light on our whole mental existence." Unlocking the mysteries of anxiety, he believed, would go far in helping us to unravel the mysteries of the mind: consciousness, the self, identity, intellect, imagination, creativity — not to mention pain, suffering, hope, and regret. To grapple with and understand anxiety is, in some sense, to grapple with and understand the human condition.

The differences in how various cultures and eras have perceived and understood anxiety can tell us a lot about those cultures and eras. Why did the ancient Greeks of the Hippocratic school see anxiety mainly as a medical condition, while Enlightenment philosophers saw it as an intellectual problem? Why did the early existentialists see anxiety as a spiritual condition, while Gilded Age doctors saw it as a specifically Anglo-Saxon stress response — a response that they believed spared Catholic societies — to the Industrial Revolution? Why did the early Freudians see anxiety as a psychological condition emanating from sexual inhibition, whereas our own age tends to see it, once again, as a medical and neurochemical condition, a problem of malfunctioning biomechanics?

Do these shifting interpretations represent the forward march of progress and science? Or simply the changing, and often cyclical, ways in which cultures work? What does it say about the societies in question that Americans showing up in emergency rooms with panic attacks tend to believe they're having heart attacks, whereas Japanese tend to be afraid they're going to faint? Are the Iranians who complain of what they call "heart distress" suffering what Western psychiatrists would call panic attacks? Are the ataques de nervios experienced by South Americans simply panic attacks with a Latino inflection — or are they, as modern researchers now believe, a distinct cultural and medical syndrome? Why do drug treatments for anxiety that work so well on Americans and the French seem not to work effectively on the Chinese?

As fascinating and multifarious as these cultural idiosyncrasies are, the underlying consistency of experience across time and cultures speaks to the universality of anxiety as a human trait. Even filtered through the distinctive cultural practices and beliefs of the Greenland Inuit a hundred years ago, the syndrome the Inuit called "kayak angst" (those afflicted by it were afraid to go out seal hunting alone) appears to be little different from what we today call agoraphobia. In Hippocrates's ancient writings can be found clinical descriptions of pathological anxiety that sound quite modern. One of his patients was terrified of cats (simple phobia, which today would be coded 300.29 for insurance purposes, according to the classifications of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, the DSM-V) and another of nightfall; a third, Hippocrates reported, was "beset by terror" whenever he heard a flute; a fourth could not walk alongside "even the shallowest ditch," though he had no problem walking inside the ditch — evidence of what we would today call acrophobia, the fear of heights. Hippocrates also describes a patient suffering what would likely be called, in modern diagnostic terminology, panic disorder with agoraphobia (DSM-V code 300.22): the condition, as Hippocrates described it, "usually attacks abroad, if a person is travelling a lonely road somewhere, and fear seizes him." The syndromes described by Hippocrates are recognizably the same clinical phenomena described in the latest issues of the Archives of General Psychiatry and Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic.

Their similarities bridge the yawning gap of millennia and circumstances that separate them, providing a sense of how, for all the differences in culture and setting, the physiologically anxious aspects of human experience may be universal.

Excerpted from My Age of Anxiety by Scott Stossel. Copyright © 2013 by Scott Stossel. Excerpted by permission of Knopf, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The Flower Sisters

by Michelle Collins Anderson

From the new Fannie Flagg of the Ozarks, a richly-woven story of family, forgiveness, and reinvention.

The House on Biscayne Bay

by Chanel Cleeton

As death stalks a gothic mansion in Miami, the lives of two women intertwine as the past and present collide.

The Funeral Cryer by Wenyan Lu

Debut novelist Wenyan Lu brings us this witty yet profound story about one woman's midlife reawakening in contemporary rural China.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.