Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' Opinion:

First Published:

Aug 2015, 336 pages

Paperback:

Dec 2016, 336 pages

Book Reviewed by:

Book Reviewed by:

Sinéad Fitzgibbon

Buy This Book

This article relates to Landfalls

The intellectually febrile period between the early 1600s and the late 1700s which saw an unsurpassed expansion in humankind's understanding of the world around us, particularly in the arenas of science (especially physics), and social and political philosophy, later came to be known as The Age of Enlightenment, also known as the Age of Reason or simply, The Enlightenment. The term signifies what was seen as an emergence from a long period of cognitive darkness, where superstitions and ignorance abounded, into the light of knowledge and awareness.

The Enlightenment was promoted by radical thinkers and philosophers in the coffee houses of Scotland and England, before spreading throughout Europe, and particularly to France. The main tenets of Enlightenment thinking were the promotion of individualism (or thinking for oneself), the rejection of traditional authoritarian institutions (such as monarchies and the Catholic Church), social hierarchies (the class system), and encouragement of religious tolerance (France had, for years, been riven with unrest between Catholicism and Protestantism). The application of reason and informed analysis was central, while blind and unthinking adherence to previously accepted societal norms was actively discouraged. Education was thought to be key to the advancement of Enlightenment principles.

The death of Louis XIV in 1715 was the spark that ignited the French Enlightenment. Louis had been an absolute monarch who had instituted a high degree of centralized government and bureaucracy, and now Gallic philosophers, inspired by their counterparts in Britain, sought to oppose the kind of power that the recently deceased king had wielded, and also to weaken the influence of the country's nobility and the dictatorial Catholic Church. Not all proponents of the Enlightenment were necessarily atheists, however; many were deists (that is, those who believed in God, or at least the existence of a single creator, but who rejected the concept of organized religion). Neither were all radical thinkers republicans; some still approved of monarchy, but rejected absolutism (that is, an autocratic monarch with the power to rule by himself without interference from a parliament or legislature). Britain's constitutional monarchy, whereby the king or queen is only a nominal head of state with all power lying with an elected assembly, was looked upon by some as an ideal compromise.

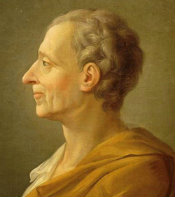

Baron de Montesquieu, known simply as Montesquieu, was one of the first leading lights of the French Enlightenment. A lawyer and a man of letters, he published a satirical pamphlet in 1721, skewering the preposterousness of certain elements of contemporary French society and lampooning the reign of Louis XIV. He would later go on to publish De l'Esprit des Lois, a dissertation on political thought, which, despite being subject to censorship, would become hugely influential in France and overseas.

Baron de Montesquieu, known simply as Montesquieu, was one of the first leading lights of the French Enlightenment. A lawyer and a man of letters, he published a satirical pamphlet in 1721, skewering the preposterousness of certain elements of contemporary French society and lampooning the reign of Louis XIV. He would later go on to publish De l'Esprit des Lois, a dissertation on political thought, which, despite being subject to censorship, would become hugely influential in France and overseas.

Following closely on Montesquieu's heels were Denis Diderot and Voltaire. Diderot was the most prominent member of a group known as the Encyclopaedists. Along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert, he founded and edited Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (Encyclopedia, or Dictionary of Arts, Sciences and Crafts). The first volume was published in 1751. By 1772, seventeen text volumes of the Encyclopaedia had been produced, as well as eleven volumes of plates (illustrations). In all, 74,000 articles were produced by 130 contributors on arts and science subjects, and became a valuable weapon in the Enlightenment's struggle against ignorance and superstition.

Voltaire (whose nom de plume was François Arouet) was a progressive, reformist writer whose political opinions landed him in jail on more than one occasion. For three years from 1726 to 1729, he had lived in exile in England. While there, he became acquainted with the English philosopher, John Locke, and Isaac Newton. Like many philosophers at the time, however, his political views were often contradictory (for example, both Voltaire and Montesquieu abhorred absolutism but also disliked democracy, and both feared the barely constrained fervor which was becoming evident among the working classes). In his most famous work, Candide, Voltaire's contradictory and ambivalent beliefs can be seen in his seeming endorsement of the Enlightenment-esque principle that all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds, before going on to dismantle the principle by inflicting a series of destructive disasters on his unfortunate protagonist, Pangloss.

Voltaire (whose nom de plume was François Arouet) was a progressive, reformist writer whose political opinions landed him in jail on more than one occasion. For three years from 1726 to 1729, he had lived in exile in England. While there, he became acquainted with the English philosopher, John Locke, and Isaac Newton. Like many philosophers at the time, however, his political views were often contradictory (for example, both Voltaire and Montesquieu abhorred absolutism but also disliked democracy, and both feared the barely constrained fervor which was becoming evident among the working classes). In his most famous work, Candide, Voltaire's contradictory and ambivalent beliefs can be seen in his seeming endorsement of the Enlightenment-esque principle that all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds, before going on to dismantle the principle by inflicting a series of destructive disasters on his unfortunate protagonist, Pangloss.

There were many other thinkers who contributed to the French Enlightenment, including such luminaries as Rousseau, Mirabeau, Talleyrand, Lafayette, and Condorcet. There was never any real consensus among these philosophes, however – some favored republicanism and democracy, while others did not, some were supportive of the French nobility, others were not. And it was this disagreement, this lack of unanimity and consensus, which would ultimately lead to the movement's destruction. By the 1750s, the Enlightenment thinkers had separated into factions according to their beliefs. It was this factionalism that, in part, fed the various divergent blocs that would go on to take part in the French Revolution.

It was, indeed, the Revolution that ultimately marked the end of the Enlightenment in France. The ideals and spirit of the Age of Reason, which were laid down in the Declaration of the Rights of Man, became distorted and corrupted. Maximilien de Robespierre exploited many of Rousseau's beliefs in particular (including his maxim that there should be a head of state, even in a republic, who had the power to overrule by force if necessary) to justify the killing spree which became known as the Reign of Terror. In the end, the French Enlightenment cannibalized itself – some radical thinkers, like Mirabeau and Voltaire, were lucky enough to have died before the Revolution broke out. Others, however, including Condorcet, the poet André Chénier, the journalist Camille Desmoulins, and the female writer, Olympe de Gouges, either died in prison or met a sticky end by Madame Guillotine's blade.

Picture of Montesquieu from Jack Miller Center

Picture of Voltaire from Huffington Post

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Landfalls. It originally ran in September 2015 and has been updated for the

December 2016 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Landfalls. It originally ran in September 2015 and has been updated for the

December 2016 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

The Funeral Cryer by Wenyan Lu

Debut novelist Wenyan Lu brings us this witty yet profound story about one woman's midlife reawakening in contemporary rural China.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.