Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to The American Lover

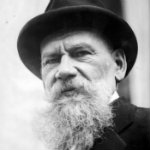

In the story "The Jester of Astapovo," from The American Lover, a simple stationmaster's life is turned upside down when the world-famous author Count Leo Tolstoy, arrives, near death. The elderly and ailing Tolstoy really did die at the remote train station after fleeing his wife weeks earlier. His obituary in The New York Times began: Tolstoy Is Dead: Long Fight Over. ASTAPOVA, Sunday, Nov. 20, 1910 — Count Tolstoy died at 6:05 this morning. The Countess Tolstoy was admitted to the sickroom at 5:50. Tolstoy did not recognize her."

Nearly a month earlier, Leo Tolstoy, one of the most famous men in Russia, had vanished from his home in the middle of the night and turned up two days later at Shamardino Convent where his sister lived as a nun. There he reportedly wept as he explained how his wife was making him crazy, how she watched his every move, stole his secret diary and crept into his study at night to rummage through his papers. After revealing his need to get away from his wife, he and his doctor again vanished until turning up at the Astapovo train station weeks later. Called by some contemporaries the "second Tsar" for his immense political influence, his disappearance became an immediate international sensation. Pursued by secret police, an army of journalists, emissaries, his family and his followers, his final days drew the attention of the entire Russian public. When he died, thousands of workers went on strike and students took to the streets in mourning.

Nearly a month earlier, Leo Tolstoy, one of the most famous men in Russia, had vanished from his home in the middle of the night and turned up two days later at Shamardino Convent where his sister lived as a nun. There he reportedly wept as he explained how his wife was making him crazy, how she watched his every move, stole his secret diary and crept into his study at night to rummage through his papers. After revealing his need to get away from his wife, he and his doctor again vanished until turning up at the Astapovo train station weeks later. Called by some contemporaries the "second Tsar" for his immense political influence, his disappearance became an immediate international sensation. Pursued by secret police, an army of journalists, emissaries, his family and his followers, his final days drew the attention of the entire Russian public. When he died, thousands of workers went on strike and students took to the streets in mourning.

Count Leo Nikolayevich Tolstoy was born on his family's estate, Yasnaya Polyana (translates to Bright Glade), 150 miles south of Moscow, on Aug. 28, 1828. His father, Count Nikolai Ilyvitch Tolstoy, was companion and friend to Czar Peter the Great.

Tolstoy studied at the University of Kazan for almost two years but left the university to take charge of his family's estates when his parents died. Shortly after, he entered the Russian Army where his perfunctory military duties allowed him to begin his long career as a novelist. He did see active service during the Crimean War and later said his first-hand experience with war was most valuable in his work as a novelist.

After the war Tolstoy went to St. Petersburg, where he was received as a nobleman, a returning hero, and a literateur. But he soon became utterly disgusted with his life there and returned to his estate, Yasnaya Polyana, dressed in peasant costume, and preached the gospel of the simple life. In 1862 Tolstoy met and wooed his young wife Sophia Behrs. While she tended house, Tolstoy spent much of his time traveling through the Russian Empire, studying social conditions. With Tolstoy having given away most of his money, the couple were too poor to have any servants; the Countess did the housework, taught the children English, French, and German, gave them music lessons, and sewed their clothes. She also helped her husband revise his books and translated them from Russian into French and German, and took care of publication of a book when it was completed.

After the war Tolstoy went to St. Petersburg, where he was received as a nobleman, a returning hero, and a literateur. But he soon became utterly disgusted with his life there and returned to his estate, Yasnaya Polyana, dressed in peasant costume, and preached the gospel of the simple life. In 1862 Tolstoy met and wooed his young wife Sophia Behrs. While she tended house, Tolstoy spent much of his time traveling through the Russian Empire, studying social conditions. With Tolstoy having given away most of his money, the couple were too poor to have any servants; the Countess did the housework, taught the children English, French, and German, gave them music lessons, and sewed their clothes. She also helped her husband revise his books and translated them from Russian into French and German, and took care of publication of a book when it was completed.

Best known for his novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina, when he wasn't writing, Tolstoy devoted his time to educating the peasantry and to working on plans for their material improvement. In 1899, he published Resurrection a novel embodying the results of years of thought. The publication led to Tolstoy's excommunication by the Holy Synod (the Orthodox Church), which had already expressed displeasure at his open disbelief in its dogmas. Tolstoy addressed this action by sending an open letter to the Czar, in which he denounced both the State Church and governmental despotism in Russia.

While Tolstoy lay dying of pneumonia in the stationmaster's bed, the Russian Cabinet in St. Petersburg discussed Tolstoy and his relations with the Church. It was reported that all present, including the Procurator of the Holy Synod, were in favor of immediately removing the ban of excommunication. While even Premier Stolypin was in favor of raising the ban, the Synod rejected the proposal, citing no indication of a change in Tolstoy's attitude, or knowledge of his desires to be restored to the faith.

Picture of Leo Tolstoy from History of Mormonism

Picture of Yasnaya Polyana mansion by Celest

Filed under Books and Authors

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to The American Lover. It originally ran in March 2015 and has been updated for the

January 2016 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to The American Lover. It originally ran in March 2015 and has been updated for the

January 2016 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

A library, to modify the famous metaphor of Socrates, should be the delivery room for the birth of ideas--a place ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.