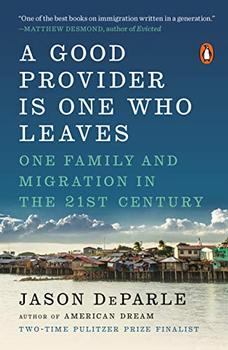

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' Opinion:

First Published:

Aug 2019, 400 pages

Paperback:

Aug 2020, 400 pages

Book Reviewed by:

Book Reviewed by:

Elisabeth Herschbach

Buy This Book

This article relates to A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves

As a young teen in the Manila slums, Rosalie, the central figure in Jason DeParle's A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves, dreamed of a path out of poverty. "Nursing, that's my choice to help and curing sickness," she wrote to DeParle. "And to earn money and go abroad."

When Rosalie scored her first overseas job almost a decade later—at a hospital in Saudi Arabia—she became just one of an estimated 10 million Filipinos who work abroad. As DeParle explains, no country promotes overseas work as heavily as the Philippines. The government facilitates oversea placements, marketing its workers to other nations. And a vast industry of vocational schools and training institutes has sprung up to channel thousands of hopeful graduates every year into fields with high demand.

Every year, more than two million Filipinos flow out of the country, taking jobs overseas to escape poverty and lack of opportunity back home. Roughly one out of every seven Filipino workers is employed abroad, the majority as temporary guest workers in the Middle East. Collectively, the money they send home to their families adds up to $32 billion USD—10 percent of the island nation's gross domestic product (GDP). These remittances—the sums migrants send home—help to lift families out of poverty and prop up an economy hobbled by extreme inequality and a legacy of political corruption. Yet overseas jobs can bring not just opportunity but peril. Horror stories of exploitation and abuse abound, especially among domestic workers—nannies, cooks, drivers, and maids—in the Persian Gulf.

Like Rosalie, many Filipino women see nursing as their safest and surest bet. Each year, roughly 19,000 Filipino nurses ship out to jobs in hospitals around the world. Less vulnerable to abuse than domestic workers, nurses also earn higher wages—especially if they are lucky enough to land a job in the United States. Pinky, a cousin of Rosalie's husband, sums up the sentiment: "Every family should have one person outside the Philippines to send money," DeParle quotes her as saying. "That's why I went to nursing school. It was our ticket out."

Rosalie's journey from a Philippine nursing school to an American hospital is rooted in a long precedent. "Migration is history's ripple effect," DeParle writes. And the preponderance of Filipino nurses in the U.S. is one ripple from its history as an American colony from 1898 to 1946. After acquiring the Philippines from Spain during the Spanish-American War of 1898, the United States established the first Philippine nursing schools. These schools followed an American curriculum and used English as the language of instruction—making Filipino nurses particularly desirable candidates for jobs in the U.S.

By 1920, a trickle of Filipino nurses had already begun arriving in the States. Their numbers then surged during the Cold War period as hospitals took advantage of the newly created Exchange Visitor Program—an effort aimed at cultural diplomacy—to solve nursing shortages. The program attempted to combat anti-American Soviet propaganda by allowing foreign workers to reside in the U.S. for a period of two years. More than 11,000 nurses from the Philippines came to America between the late 1950s and 1960s. Many got waivers from their employees or found other ways to stay beyond two years.

Today, thanks to chronic nursing shortages, Filipino nurses continue to be in high demand. Nationwide, roughly eight percent of America's registered nurses were born and trained overseas. More than one-third of these nurses are from the Philippines. The U.S. is far from the only country where they are so well-represented. Visiting a London-area hospital, Prince Philip joked to the nursing staff, "The Philippines must be half-empty—you're all here."

At least in the U.S., foreign nurses are an interesting counterpoint to the argument commonly voiced by the immigration-wary—that immigrants will take jobs away from Americans and depress wages. Nurses like Rosalie are filling vital unfilled jobs, rather than taking jobs away. And because they tend to have more education than their American-born counterparts, they often command higher salaries—they are the opposite of cheap labor. "I hear a lot of flak about these people taking jobs," an employee at Rosalie's hospital said. "Well, if we had qualified nurses, they wouldn't be coming here."

Filed under Society and Politics

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves. It originally ran in September 2019 and has been updated for the

August 2020 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves. It originally ran in September 2019 and has been updated for the

August 2020 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

The House on Biscayne Bay

by Chanel Cleeton

As death stalks a gothic mansion in Miami, the lives of two women intertwine as the past and present collide.

The Flower Sisters

by Michelle Collins Anderson

From the new Fannie Flagg of the Ozarks, a richly-woven story of family, forgiveness, and reinvention.

The Funeral Cryer by Wenyan Lu

Debut novelist Wenyan Lu brings us this witty yet profound story about one woman's midlife reawakening in contemporary rural China.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.