Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Book Reviewed by:

Book Reviewed by:

Natalie Vaynberg

Buy This Book

This article relates to Immune

A staggering number: over 34,000 organ transplants were performed in the U.S. in 2017 alone. Another staggering number: 115,000 people are currently waiting for life-saving organ transplants in the U.S. As the medical techniques and success rates continue to improve, organ transplants are quickly becoming a tremendous lifeline for some of the population. Anyone who has had to consider an organ transplant has been, of course, informed of all the physical risks and dangers involved, but might there be something else to consider?

A staggering number: over 34,000 organ transplants were performed in the U.S. in 2017 alone. Another staggering number: 115,000 people are currently waiting for life-saving organ transplants in the U.S. As the medical techniques and success rates continue to improve, organ transplants are quickly becoming a tremendous lifeline for some of the population. Anyone who has had to consider an organ transplant has been, of course, informed of all the physical risks and dangers involved, but might there be something else to consider?

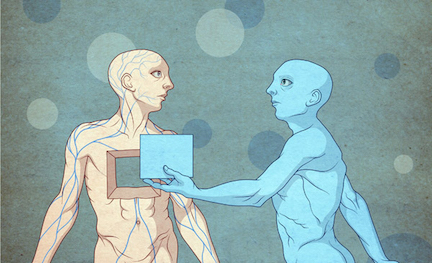

There is a psychological component to organ transplants as well. In many cases, organ recipients experience feelings of guilt – they have survived through the benefit of someone else's organ, someone else's death. This feeling is anticipated and, in many cases, alleviated by some form of contact with the donor's family; both parties might then begin to feel that there is a greater purpose at work. But what if the impact of a donated organ is something much less understandable? What if those donated organs have a direct effect on the personality of their new owner? It may sound like a preface to a horror movie, but it may just have scientific basis.

Many stories have been told of organ recipients taking on new hobbies, exhibiting new predilections, even adopting entirely unprecedented behaviors – all aligning with those of their donor. For example, Claire Sylvia in Massachusetts began to experience cravings for fried foods and beer, then discovered her donor was an 18-year old man who enjoyed both. Amy Tippins in Georgia, after a liver transplant, found herself attracted to hardware stores and do-it-yourself projects, much like her donor!

These kinds of stories have had a profound effect on the collective psyche. Research shows that as many as 49% of potential organ recipients worry that they will take on characteristics of their donors. Other studies have discovered that some people would rather turn down a transplant than receive an organ from a murderer or an animal.

The scientific community has generally scorned such fears – aside from anecdotes, there has been little in the way of evidence suggesting such a transfer of personality traits from donor to recipient. However, a new study on cellular memory might just be the first step to confirming this pervasive claim.

There is a general understanding that memories live in synapses – spaces where one neuro cell connects to another. Memories are dependent on these synapses and the weaker the synapse, the foggier the memory. However, scientists studying sea slugs at UCLA discovered that even when the synapse-building response was inhibited chemically, the slugs' neurons were able to recreate the same number of synapses as they had previously established outside of the study. This means that some element of memory may not live in the synapse after all, it may exist in the cell body. If this is true, cells may remember their previous home, their previous desires, and they might send those signals to a new brain. But cellular memory is currently only a theory in its formative stages, and decades of scientific knowledge seek to deny the findings. It may be difficult to counter the evidence. For example, in one study, only 6% of heart recipients had experienced drastic personality changes while the overwhelming majority has felt little to none?

It is important to note a few additional considerations. In another study, 73% of recipients of hearts felt a drastic, positive shift in life perception – meaning that they may be more likely to take on new hobbies or experiences. Additionally, although recipients and donor families are restricted, by confidentiality policies, to anonymous contact for at least the first year after the donation, there are certainly ways to circumvent the rules. Remember Claire Sylvia, who discovered a new-found love of beer and fried chicken? She tracked down her donor by simply doing an online search for accidental deaths near the time of her transplant surgery! What else could she find with a simple Google search?

The psychological impact of organ transplants is vast and, as yet, not fully understood. Maybe an organ donation can, in fact, result in new personality traits, and maybe, as Catherine Carver suggests in Immune: How Your Body Defends and Protects You, our fundamental feelings of identity are more closely tied to our internal organs than we ever suspected.

Filed under Medicine, Science and Tech

![]() This article relates to Immune.

It first ran in the January 24, 2018

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This article relates to Immune.

It first ran in the January 24, 2018

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

The Funeral Cryer by Wenyan Lu

Debut novelist Wenyan Lu brings us this witty yet profound story about one woman's midlife reawakening in contemporary rural China.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.