Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to All the Light We Cannot See

History of Saint Malo

The siege and subsequent burning of Saint Malo during World War II is intrinsically bound to the island's history. Saint Malo is a scenic and historic port city nestled in the crook of Brittany's arm on the North coast of France. According to "St-Malo an independent travel guide," Saint Malo was founded in the 1st century BCE, a short distance to the south of the current city. Coveted for its strategic location at the mouth of the Rance River, the town was first fortified by Celtic tribesmen and later by the Romans. In the sixth century, Celtic Bishop, Maclou or MacLow, who was later canonized as Saint Malo, co-founded a monastic order on the rocky island that would later take his name. In the twelfth century, Bishop Jean de Chatillon added thick ramparts, turning the town into the walled city-fort that remains today.

The siege and subsequent burning of Saint Malo during World War II is intrinsically bound to the island's history. Saint Malo is a scenic and historic port city nestled in the crook of Brittany's arm on the North coast of France. According to "St-Malo an independent travel guide," Saint Malo was founded in the 1st century BCE, a short distance to the south of the current city. Coveted for its strategic location at the mouth of the Rance River, the town was first fortified by Celtic tribesmen and later by the Romans. In the sixth century, Celtic Bishop, Maclou or MacLow, who was later canonized as Saint Malo, co-founded a monastic order on the rocky island that would later take his name. In the twelfth century, Bishop Jean de Chatillon added thick ramparts, turning the town into the walled city-fort that remains today.

The inhabitants of Saint Malo, called Malouins, have always been known for their fierce independence. They fought whoever ruled them - Brittany, the Dutch, the French and the English - and survived briefly as an independent state. Since some time around the fourteenth century (depending on the source you use) Malouins began plundering ships for their bounty, and during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Saint Malo was home to the famous corsairs, mercenary sailors who, in return for immunity from prosecution and a share of the bounty, attacked the ships of France's enemies during wartime.

The Siege of Saint Malo

By the time of the corsairs, Saint Malo had become a virtually impenetrable fort. The city itself was walled, and forts were established at strategic locations to control entrance to the city from the sea as well as the Rance River. The corsairs also constructed a complex network of tunnels and underground storerooms to hide and store their bounty. It was this impenetrability, as well as access to underground structures that could be turned into command bunkers and hospitals, that made the city vital to German interests and made conquest by the Americans so difficult. The German garrison commander was Colonel Andreas von Aulock, who was a veteran of the hand-to-hand fighting in Stalingrad and vowed to "defend St. Malo to the last man even if the last man had to be himself." He commanded his troops from one of the forts, La Cité Fort, which the Germans had expanded into a vast network of tunnels and interconnected bunkers.

By the time of the corsairs, Saint Malo had become a virtually impenetrable fort. The city itself was walled, and forts were established at strategic locations to control entrance to the city from the sea as well as the Rance River. The corsairs also constructed a complex network of tunnels and underground storerooms to hide and store their bounty. It was this impenetrability, as well as access to underground structures that could be turned into command bunkers and hospitals, that made the city vital to German interests and made conquest by the Americans so difficult. The German garrison commander was Colonel Andreas von Aulock, who was a veteran of the hand-to-hand fighting in Stalingrad and vowed to "defend St. Malo to the last man even if the last man had to be himself." He commanded his troops from one of the forts, La Cité Fort, which the Germans had expanded into a vast network of tunnels and interconnected bunkers.

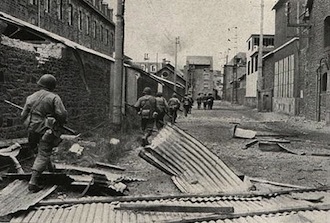

The attack against Saint Malo began on August 3rd and 4th, 1944. From the account Into the Hornet's Nest: "The 331st with the 908th Field Artillery Battalion attacked the northeastern end of the line, while the 330th with the 323rd Field Artillery attacked the center. The 329th and 322nd Field Artillery attacked on the south." Advance proved difficult; Germans had covered all favorable approaches to the city with minefields and barbed wire, and a network of big guns installed in the ancient pillboxes defended against American incursion.

On August 6th, a German minesweeper shelled the Cathedral of Saint Vincent inside the city of Saint Malo, destroying the spire and causing substantial structural damage. On August 7th, the Germans blew up the harbor installations, including the massive lockgates, and scuttled a number of vessels, thus rendering the harbor useless if the Allies took it. They also rounded up all Malouin males between the ages of 16 and 60, purportedly to revenge an attack in which French "terrorists" had fired on German soldiers, and interned them in Fort National, where they remained without food or water until August 13th. Unfortunately, the fort was in the line of fire between the Americans, who were bombarding the city with heavy artillery shells, and the German big guns. An American shell hit Fort National, killing 18 prisoners.

August 7th also saw the spread of fires throughout the city; they could not be extinguished because the Americans, in an attempt to hasten German surrender, had cut the water supply. The ancient buildings of Saint Malo burned for a week, engulfing the town in a pall of black smoke. The fires were aided by the construction of the houses: thick wooden beams to support walls and ceilings. From The Burning of Saint Malo by Philip Beck: "Thirty thousand valuable books and manuscripts were lost in the burning of the library and the paper ashes were blown miles out to sea." By the time von Aulock finally surrendered on August 17th, "Of the 865 buildings within the walls only 182 remained standing and all were damaged to some degree." An eyewitness account:

August 7th also saw the spread of fires throughout the city; they could not be extinguished because the Americans, in an attempt to hasten German surrender, had cut the water supply. The ancient buildings of Saint Malo burned for a week, engulfing the town in a pall of black smoke. The fires were aided by the construction of the houses: thick wooden beams to support walls and ceilings. From The Burning of Saint Malo by Philip Beck: "Thirty thousand valuable books and manuscripts were lost in the burning of the library and the paper ashes were blown miles out to sea." By the time von Aulock finally surrendered on August 17th, "Of the 865 buildings within the walls only 182 remained standing and all were damaged to some degree." An eyewitness account:

The sky is black smoke, pieces of burnt paper flying in the city and come to the Fort National. Saint-Malo became a blaze burning, late at night we are to contemplate the fire which consumes the ruin of one of the most picturesque cities in the world. In a few days to the efforts of the generations that succeeded vanishes for ever before our eyes alarmed."

The cause of the fires is of some debate. Philip Beck argues that the fires came from, "A ring of U.S. mortars" that rained down incendiary shells onto the city. This version is corroborated by the eyewitness accounts and examination of spent incendiary shells that led to von Aulock's acquittal on charges of, "the barbaric act of burning the corsairs' city."

Following the end of WWII, Saint Malo was rebuilt to replicate the old city, thus preserving its long and proud history. In some cases, this was done literally "stone by stone." Many of the old ramparts and pillboxes remain, and there is a museum honoring the history of the ancient city. Today, Saint Malo is a tourist destination, one of the most popular in Brittany. It is the #1 port in North Brittany and has the highest concentration of restaurants in that region.

Following the end of WWII, Saint Malo was rebuilt to replicate the old city, thus preserving its long and proud history. In some cases, this was done literally "stone by stone." Many of the old ramparts and pillboxes remain, and there is a museum honoring the history of the ancient city. Today, Saint Malo is a tourist destination, one of the most popular in Brittany. It is the #1 port in North Brittany and has the highest concentration of restaurants in that region.

Map of Saint Malo, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Painting of French corsairs in 1806 by Maurice Orange .

Siege on Saint Malo, courtesy of www.angelfire.com.

Saint Malo, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Filed under Places, Cultures & Identities

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to All the Light We Cannot See. It originally ran in May 2014 and has been updated for the

May 2014 edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to All the Light We Cannot See. It originally ran in May 2014 and has been updated for the

May 2014 edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.