Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

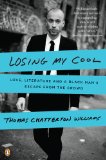

How a Father's Love and 15,000 Books Beat Hip-hop Culture

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' Opinion:

First Published:

Apr 2010, 240 pages

Paperback:

Apr 2011, 240 pages

Book Reviewed by:

Book Reviewed by:

BookBrowse First Impression Reviewers

Buy This Book

Chapter One

The Discovery of What It Means

to Be a Black Boy

It was wintertime, early in the morning. I was in the third grade,

standing on the rectangular asphalt playground behind Holy

Trinity Interparochial School in Westfield, New Jersey, palming a

tennis ball, waiting. Ned, nearsighted and infamous for licking the

dusty soles of his penny loafers in the back of social studies class,

was splayed against the cold orange brick wall of the school building.

He had his head down and hands up, legs akimbo with his butt

out, like a South American mule bracing herself to be searched

by border patrol. “Not so hard!” he cried, glancing back over his

shoulder through smudged Coke-bottle lenses.

“Put your head down!” another boy yelled.

“Fine, just do it and get it over with, then,” Ned muttered.

“Head down!” the boy said. I wound my arm back and let fly a

fastball that seemed to hang in the air for a second before ricocheting from the small of Ned’s back like a Pete Sampras ace off some hapless ball boy at Wimbledon. Ned jerked upright and howled in pain. All my classmates screamed and high-fived me as

the bell rang and we rushed to grab our book bags and line up in

size order before our teachers came to lead us indoors. I was still

the undisputed king of Butts-Up, I thought to myself as I pulled my

Chicago Bulls Starter jacket over my uniform. Standing in line, waiting

for the younger grades to file past, I began mumbling to myself

bits of a song by Public Enemy, a song that my older brother had

been playing at home and that had gotten stuck in my head that

week like the times tables or the Holy Rosary. “Yo, nigga, yoooooo,

nigga, yoooo-oooooo, niiiigga . . .” I repeated the refrain over and

over under my breath, unthinkingly, as I relived in my mind’s eye

the glorious coup de grace, the deathblow I’d just dealt Ned from

over ten yards away—Blaow!

“But you’re a nigger, too,” a voice said from behind me, and I half

made out what I’d just heard, but not fully. I went on singing my

song, which I couldn’t claim to understand on any level, but which

somehow made me feel cool as hell, and that was all that mattered.

The voice repeated itself, louder this time: “But you’re a nigger,

too, Thomas, aren’t you?”

“Huh?” I said, pivoting to see Craig standing there, his dirtyblond

hair cut by his mother’s Flowbee into the shape of an upsidedown

serving bowl, like a medieval friar without the bald spot.

“What did you just say?”

“You’re a nigger, too, right, so how can you say that?”

“How can I say what?”

“‘Yo, nigga, yo, nigga’; how can you say that when you’re a nigger,

too, right?”

My mother is white, my father black. They met in San Diego in the

late 1960s. Both were entrenched on the West Coast front of what

at the time was called the War on Poverty. After San Diego, they

went up to Los Angeles. From L.A. they made their way north and

my father pursued doctoral studies in sociology at the University

of Oregon. In 1975, and over my maternal grandfather’s dead body,

they were married in Eugene at the county courthouse. They had

little money, fewer blessings, and plenty of love. Later, they moved

again to Spokane and my mother, Kathleen, gave birth to their first

child, Clarence, named for my father. From Spokane the family continually

moved east: first to Denver, then to Albany, then to Philadelphia,

and finally to New Jersey, where I was born in 1981.

When I was one year old, my father switched professions and

the family moved again, this time from Newark, where he had been

running antipoverty programs for the Episcopal Archdiocese and

my mother had been raising my brother and me, to Fanwood, a

small suburb thirty minutes to the west on U.S. Route 22. Fanwood,

like the space inside a horseshoe, is bordered on three sides by the

much larger township of Scotch Plains, and these two municipalities

by and large function as one. They share a train station and

public school system and together act as a kind of buffer ground

between wealthy Westfield to the east and poor Plainfield to the

west. Riots and waves of white flight long ago left Plainfield a

vexed cross between a legitimate inner-city ghetto—with all the

requisite crime, poverty, and hopelessness that go with that—and

an emergent middle-class suburb that in many ways resembles

Westfield, except for the condition of the houses and the color of

the residents. No such white flight occurred in Fanwood, Scotch

Plains, or Westfield, although like so many small towns in New

Jersey, they had their designated black pockets.

Excerpted from Losing My Cool by Thomas Chatterton Williams. Copyright © 2010 by Thomas Chatterton Williams. Excerpted by permission of Penguin Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The House on Biscayne Bay

by Chanel Cleeton

As death stalks a gothic mansion in Miami, the lives of two women intertwine as the past and present collide.

The Flower Sisters

by Michelle Collins Anderson

From the new Fannie Flagg of the Ozarks, a richly-woven story of family, forgiveness, and reinvention.

The Funeral Cryer by Wenyan Lu

Debut novelist Wenyan Lu brings us this witty yet profound story about one woman's midlife reawakening in contemporary rural China.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.