Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to Spider Love Song and Other Stories

Large-scale Chinese immigration to America began in the mid-1800s, partly in response to economic instability in China during the Taiping Rebellion, a civil war that lasted from 1850-1864. Like many others, Chinese immigrants were also drawn

by the California Gold Rush.

Large-scale Chinese immigration to America began in the mid-1800s, partly in response to economic instability in China during the Taiping Rebellion, a civil war that lasted from 1850-1864. Like many others, Chinese immigrants were also drawn

by the California Gold Rush.

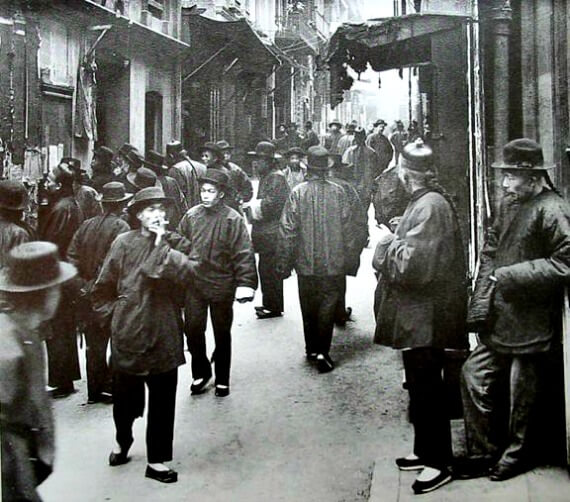

After the gold rush ended, many Chinese people stayed on in the U.S. to work jobs or start their own businesses. During this time, the Chinese gained a reputation as hard workers who would perform cheap labor. The truth was that many Chinese workers were exploited and given little or no choice in the conditions of their labor, being paid substantially less than white workers and forced to take on more dangerous tasks. When economic depression hit the country in the 1870s, white laborers would come to view the Chinese as competition. This set the stage for Congress passing the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

This act drastically limited Chinese immigration, preventing Chinese laborers from entering the U.S. and only making exceptions for certain individuals, such as students and tourists. Initially, the Exclusion Act was only passed for 10 years, but it was subsequently extended in 1892 and 1902, and made indefinite in 1904. As a result, the Chinese population in America declined sharply over the last decade of the 19th century and first decade of the 20th. Chinese people in the U.S. suffered additional restrictions during this time, such as being required to carry identity certificates, and those trying to enter the country were often deported or detained. The Angel Island Immigration Station, opened in 1910, was known for processing European immigrants quickly but holding Chinese immigrants in unsanitary conditions for weeks or even months.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was finally repealed in 1943 as a means of strengthening the U.S. alliance with China during World War II. Chinese immigration remained highly limited for long after this, with a set quota of only 105 visas per year. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, however, which threw out the quota system discriminating against immigrants based on nationality, would contribute to revived Chinese immigration to the U.S. in the coming decades.

Both before and after the Exclusion Act, Chinese laborers played a significant role in building major parts of U.S. infrastructure, including the Central Pacific Railroad running between Sacramento and Utah, which joined with the Union Pacific in 1869 to become the first transcontinental railroad in the country. In Nancy Au's story "Lincoln Chan: Pear King," which appears in her collection Spider Love Song and Other Stories, the main character's father likes to talk about how their forebears constructed levees on Andrus Island, alluding to the work done in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta in the 1880s to make its wetlands habitable and farmable. Au's title references a second-generation Chinese American pear farmer from the area, after whom her main character is named. The man's family still maintains the farming tradition he established. This real-life story shows the deep multi-generational ties Chinese Americans have formed to various regions of the U.S. despite continual social and legal discrimination.

San Francisco's Chinatown, courtesy of Immigration to the United States

Filed under Places, Cultures & Identities

![]() This article relates to Spider Love Song and Other Stories.

It first ran in the November 13, 2019

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This article relates to Spider Love Song and Other Stories.

It first ran in the November 13, 2019

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.