Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

'You need new ones.' I finger the murky lace of one battered specimen.

'Why? Who's looking at them?'

Below us, in the building grounds, a baby is crying in her ayah's arms. The woman rocks her maniacally while talking to the watchman. The cries are like that of an animal in pain. We sit silently, waiting for the baby to tire, for her vocal cords to give way, but the screams continue without intermission. The ayah keeps rocking, panting, in panic, perhaps hoping her employers in the building above don't hear.

'I don't understand why you won't buy new bras,' I say. I wasn't planning on returning to this, but somehow I have. The baby is still crying. I wonder what the child could possibly want, and why it seems like the only thing that matters.

'I have to be an example.'

'An example for what?'

'For you. You don't have to care what others say all the time. Not everything is a show for the world. Sometimes we do things just because we want to.'

If our conversations were itineraries, they would show us always returning to this vacant cul-de-sac, one we cannot escape from.

I start by taking the bait: 'What have I done that I don't want to do?

She feigns benevolent dismissal: 'Anyway, let's not get into all of that.'

The refusal to let things go: 'Then why did you bring it up?'

More dismissal and rejection: 'Leave it, it doesn't matter.'

The outright anger: 'It matters to me.'

The rest unfolds predictably. She asks why I am always after her, behind her, chasing after her like a rabid dog with my fangs out. Don't I have anything better to do, she asks, than bully my own mother?

I do not hesitate for a moment when I tell her she only knows how to think about herself. Her expression moves towards injury but turns back, and she says, 'There's nothing wrong with thinking about oneself.'

I halt at the usual impasse. Where do we go from here?

I want to tell her all the things that are wrong with it, but can never find the words. I want to ask her what's so terrible about doing what other people want, with making another person happy. Ma always ran from anything that felt like oppression. Marriage, diets, medical diagnoses. And while she did that, she lost what she refers to as excess fat. She has no interest in being lean of body – but she doesn't need repressed know-nothings around her, she says. The feeling has become mutual. Certain contemporaries at the Club refuse to acknowledge Ma. The elder relatives, who might have had a soft spot for the child they remembered, are infirm or dead. Yes, Ma has people around her, people who love her, but to me they seem few. To me, we have always been alone.

There are repercussions for living the life she's chosen. I wonder if the loss is worth it, and if she believes it's worth it. I wonder what she feels after I leave to go back to Dilip and she looks around her house. Maybe this isn't her choice at all, but another path she has mapped over and over, one she cannot unlearn. I want to ask her if, in all the years she has run away, any part of her screams come after me? Does she want to be caught, brought back and convinced that she is important, that she is necessary?

But these questions dissolve when I see her leaning back in her chair, eyes closed, humming to the soundtrack of the crying baby and sipping her sour water.

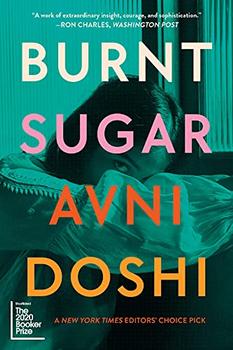

Excerpt from the new book Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi published by The Overlook Press © 2021

Finishing second in the Olympics gets you silver. Finishing second in politics gets you oblivion.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.