Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' Opinion:

First Published:

Nov 2008, 304 pages

Paperback:

Nov 2009, 304 pages

Book Reviewed by:

Book Reviewed by:

Amy Reading

Buy This Book

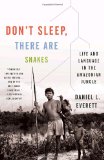

This article relates to Don't Sleep, There Are Snakes

In Don't Sleep, There are Snakes, the elephant in the room—or rather, the elephant in the Amazonian jungle—is the noted American linguist, Noam Chomsky. To put it far too simply, Chomsky and Everett are feuding over which has supremacy in linguistics: genetics or culture, nature or nurture.

Chomsky's theory of universal grammar, which has dominated linguistics for

the last forty decades, hypothesizes that the human brain comes pre-equipped

with a set of rules for constraining language. The theory arose from a question:

how can a child who is acquiring language learn what is ungrammatical, if the

only speech she hears is grammatical and correct? Adults do not teach language

to children by speaking improper sentences and then marking them as such, so how

do children know what formulations violate their languages' grammar? The theory

of universal grammar answers that this knowledge has been evolutionarily mapped

onto our brains. It is as if the rules governing the movement of chess pieces

were implanted in the human brain, so that children grow up only seeing

allowable moves when they look at the board. Because this "language instinct"

is genetic, Chomsky further hypothesizes that all of the world's languages share

an underlying structure, despite their dizzying variations in the way meaning is

expressed.

In a 2002 article in the journal Science, Chomsky, Marc D. Hauser, and

W. Tecumseh Fitch took this theory one step further by pinpointing a specific

feature of this universal grammar which distinguishes human communication from

that of other animals. After reviewing the studies done on dolphins, songbirds,

apes, and monkeys, they state, "It seems relatively clear, after nearly a

century of intensive research on animal communication, that no species other

than humans has a comparable capacity to recombine meaningful units into an

unlimited variety of larger structures, each differing systemically in meaning."

Human language owes its capacity for infinite expression to the property of

recursion, in which meaning can be embedded with meaning. Chomsky explains,

"There is no longest sentence (any candidate sentence can be trumped by, for

example, embedding it in ‘Mary thinks that…'), and there is no non-arbitrary upper bound to sentence length. In these respects, language is directly

analogous to the natural numbers." Chomsky calls this "discrete infinity" or

"infinite generativity," but a layperson would call it creativity.

Everett has sent a flare across the sky of Chomsky's kingdom with his

announcement that the Pirahãs entirely lack recursion in their language. He

discovered that a sentence with a relative clause (such as: The man who was tall

came into the house) is unavailable in their grammar and can only be expressed

in two simple sentences (The man came into the house. He was tall). But one day,

as he watched a Pirahã man making an arrow for his fishing spear, he heard

something which electrified him. The man said, "Hey Paitá, bring back some

nails. Dan bought those very nails. They are the same." These three sentences

could be translated into English as, "Bring back the nails that Dan bought."

Everett realized that the third sentence acted as a kind of equal sign to

indicate to the listener that the nails in the first sentence were the same as

the nails in the second sentence.

The implications of this tiny third sentence are incredibly far-reaching. It

indicates that the Pirahãs can say everything an English speaker can say, but

without recursion. Therefore recursion is not the fundamental characteristic of

human speech. And therefore, Everett writes, "There does not have to be a

specific genetic capacity for grammar; the biological basis of grammar could

also be the basis of gourmet cooking, of mathematical reasoning, and of medical

advances. In other words, it could just be human reasoning."

For an encapsulated version of Don't Sleep, There are Snakes, try John

Colapinto's

feature story on Daniel Everett in the New Yorker. To hear

samples of Pirahã speech and browse a few pictures of the people, visit the

author's website.

Filed under Cultural Curiosities

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Don't Sleep, There Are Snakes. It originally ran in January 2009 and has been updated for the

November 2009 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Don't Sleep, There Are Snakes. It originally ran in January 2009 and has been updated for the

November 2009 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

The House on Biscayne Bay

by Chanel Cleeton

As death stalks a gothic mansion in Miami, the lives of two women intertwine as the past and present collide.

The Flower Sisters

by Michelle Collins Anderson

From the new Fannie Flagg of the Ozarks, a richly-woven story of family, forgiveness, and reinvention.

The Funeral Cryer by Wenyan Lu

Debut novelist Wenyan Lu brings us this witty yet profound story about one woman's midlife reawakening in contemporary rural China.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.