Reading Group Center

- Home •

-

Books by Category •

- Imprints •

- Authors •

- News •

- Videos •

- Media Center •

- Reading Group Center

Newsletter

Sign up for the Reading Group Center Newsletter

Reading Group Resources

Reading Group Guides

Reading Group Tips

News & Features

Connect with Us

One Book, One Community

Community-based reading initiatives are a growing trend across the country, and we're pleased to support these programs with a wide range of resources.

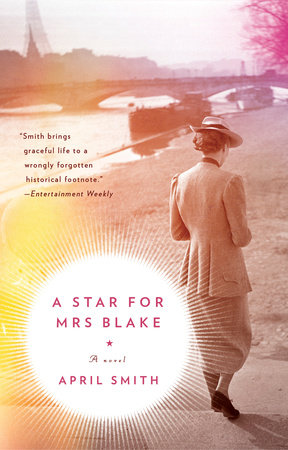

Q&A: April Smith Shines a Light on a Nearly Forgotten Historical Footnote

“Writing A Star for Mrs. Blake must have been a labor of love and it shows on every page.” So says Nelson DeMille about April Smith’s captivating novel—and he couldn’t be closer to the truth. Smith has brought to life a nearly forgotten historical footnote that’s very personal to her: the story of fallen soldiers’ mothers and widows, thousands of whom traveled to France after World War I to visit the graves of their loved ones. They were accompanied on those journeys by military officials, men like Lieutenant, later Colonel Thomas Hammond, whose journal Smith discovered twenty-five years ago. What she found in its pages left an indelible mark, inspiring her to give voice to the women whose pain and quiet fortitude were all but omitted from the historical record. Here, April Smith answers questions about her novel, and reflects on women’s sacrifice during the war, the importance of righting the wrongs of history, and what she hopes readers take away from her story.

RGC: A Star for Mrs. Blake offers a female perspective on the aftermath of the Great War. What have historical accounts overlooked that you wanted to enlighten readers about through the novel?

AS: The untold story of the Great War is how the lasting burden of all that destruction was carried, for the rest of their lives, by the mothers and widows of those who fought and died; and the even bigger story is how their grief was briefly recognized, exploited, and then forgotten.

In the early 1930s, the US government sponsored an extraordinary program called the American Gold Star Mothers pilgrimages. Almost 7,000 bereaved mothers traveled to Europe, first class on ocean liners, to visit the graves of their loved ones in the American military cemeteries overseas. It was the middle of the Depression and made great news. The pilgrims were photographed in their white dresses carrying roses, and gave radio talks on how well they were treated—then everything vanished, particularly the interest in women’s sacrifice during the war. Nowhere are they mentioned in history books, and not one person I spoke to while writing this novel had ever heard of the pilgrimages—not even military personnel, including a decorated general.

What does this say about the role of women in war? My feeling is that, despite all the hoopla, the WWI Gold Star Mothers didn’t really have a voice (they didn’t even have the vote until 1920) and that they deserved to be heard above the roar of conventional accounts. We know all about the inhuman weaponry and the terrible, heroic actions and pointless deaths—but what about that lone Gold Star in a kitchen window in small-town America, thirteen years later? To me, that mother’s story is not a sidebar, but central to the telling of this war, and every war.

RGC: On p. 21, you describe the powerful kinship among Gold Star Mothers: “More than 100,000 American mothers lost their cherished sons. Each had been alone; but they were alone no longer.” Will you tell us more about how you were inspired by the Gold Star Mothers organization, still extant today?

AS: I was struck most deeply by the unconditional love and acceptance members of the American Gold Star Mothers, Inc., provide for each other. Everyone has suffered the same loss, and that creates a sense of safety. I was privileged to get to know a group of Navy moms while their sons and daughters were deployed in Afghanistan. To witness their bravery and support of each other in real time was inspirational. The ability of women to transcend barriers is enormously powerful. It can—and does—change the world. The orchestration of the characters in A Star for Mrs. Blake was quite deliberate, from top to bottom in the accepted social order, and that was to show how isolated they were going in, and how difficult it was to be thrown into such an emotional and vulnerable state with only their own resources to keep them halfway sane…. The answer they found was to take a risk and forge connections.

RGC: You drew on the diary of an army colonel who accompanied a party of Gold Star Mothers on their pilgrimage to France. What was the most surprising or touching moment in his written account? How did you represent it in the novel?

RGC: You drew on the diary of an army colonel who accompanied a party of Gold Star Mothers on their pilgrimage to France. What was the most surprising or touching moment in his written account? How did you represent it in the novel?

AS: The journal of Thomas Hammond was handwritten in large sloping letters in a Wanamaker’s Diary when he was a twenty-four-year-old lieutenant. Most touching to me was his sensitivity to the women in his charge—not without youthful irony:

June 6, 1932: “Mrs. Straus issued an ultimatum demanding room with bath so I gave her the nurses’. That pleased the nurses! Ha! Ha! Drove to Brookwood. Very beautiful. Mrs. Dalton laid one wreath and I slung the other. Mrs. Goldstein needed consoling. I consoled.”

The following day: “They’re popping fast now. Mrs. Armstrong alleged to have stolen Mrs. Reinhold’s face powder. They are now living separately. We had an extra room or I would have slept in the park. It’s funny now but not a little while ago. I was free today, bought shirts.”

The diary gave me entrée to the story from the viewpoint of a bright young man. It is a very human rendering. You can see friction and petty disagreements in the novel, which were fun to write and gave the narrative some needed comic relief!

RGC: A Star for Mrs. Blake is a novel about a little-known episode in our history, but the poignant story it tells is very much relevant today. Have you heard from any fallen soldiers’ mothers who’ve read it?

AS: Yes, I have met many contemporary Gold Star Mothers who lost children in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as their husbands and families. It’s been enormously gratifying to hear them say Cora Blake’s story is true to their experience. I was honored to attend a T.A.P.S.—Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors—seminar attended by 2,400 people, in which we had a “book club” of military parents who had lost children. A Star for Mrs. Blake was the touchstone for discussion. It surprised me that many came in couples, mothers and fathers.

Here is a sample of the type of responses I’ve gotten from military moms:

“I just finished your wonderful book. I enjoyed the story and praise your dedication to complete the book. I will be recommending it as a must-read to all my friends and my book club. Thank you for giving recognition to those who have given the ultimate for the freedom we have today. From a mom whose son did serve in a war but came home.” K.M., Oregon

Interestingly, I’ve also heard from readers whose grandmothers went on the pilgrimages, but they never understood what it was all about. Some have found keepsakes and recovered family histories. My favorite is about the lady who missed the boat in New York harbor, and had to be taken by tug a mile out to sea—and then climb a ladder into the ship!

I’d love reading groups to share their stories at april@aprilsmith.net.

RGC: There are myriad historical, political, and universal issues in A Star for Mrs. Blake that warrant discussion. But what is one aspect of the novel to which you’d like reading groups to pay close attention?

AS: One of the central questions I wanted to explore was the nature of the bond between mothers and their children, specifically, because that was the nature of the time, between mothers and sons. I’d like to know how reading groups feel about the responsibility of mothers when it comes to their children’s choice to go to war. We nurture our children and let them go—but how far and when? You’ll note that Sammy is only sixteen when he runs away and enlists—underage, and just on the tender border of adulthood. If you were Cora, the single mom of an only child, and you could have had the conversation with her son that she couldn’t—what would you have said? Would you have tried to stop him? I guess the question is really about the bond of love in our society. Can it prevail?