by Edouard Louis

One question took center stage in my life, it focused all of my thoughts and occupied every moment when I was alone with myself: how could I get this revenge, by what means? I tried everything.

Édouard Louis longs for a life beyond the poverty, discrimination, and violence in his working-class hometown—so he sets out for school in Amiens, and, later, university in Paris. He sheds the provincial "Eddy" for an elegant new name, determined to eradicate every aspect of his past. He reads incessantly; he dines with aristocrats; he spends nights with millionaires and drug-dealers alike. Everything he does is motivated by a single obsession: to become someone else. At once harrowing and profound, Change is not just a personal odyssey, a story of dreams and of "the beautiful violence of being torn away," but a vividly rendered portrait of a society divided by class, power, and inequality.

Édouard Louis's 2014 debut novel, The End of Eddy—an instant literary success, published when Louis was just twenty-one—follows the life of a gay youth in a small, poor factory town in northern France. Based on Louis's own life, the novel details the cruelty hurled at Eddy—by his neighbors, peers, and especially his own family—for his homosexuality: slurs, beatings, taunts, gossip. But while Eddy's bullies and family are no sympathetic figures, the novel is as much about the systematic oppression that Eddy's village faces as it is about their homophobia. The novel is full of bracing anecdotes of the indignities of poverty: Eddy's family bathing in the same tub to save water; Eddy begging the grocer to extend their credit so they could eat dinner; Eddy's father breaking his back at his factory job and losing the family's sole source of income. The cruelty, alcoholism, and physical violence of this world is a result of its denizens' circumstances, if not excused by them: violence begets violence (see Beyond the Book).

While reading The End of Eddy, we know how it ends, because of its author's biography: Eddy will escape the small town in which he was never accepted, attend the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, change his name from Eddy Bellegueule to Édouard Louis, and become a celebrated writer at age twenty-one. In fact, the novel doesn't make it that far—it closes with Eddy's acceptance into a performing high school in the nearby city of Amiens, the first step in his escape. "I was already far away; I had already left their world behind," he says upon receiving his acceptance letter.

Change, Louis's latest novel, picks up where The End of Eddy leaves off and finishes the story, detailing the difficult, intensely intentional process by which Louis's autofictional alter ego transforms himself from Eddy to Édouard and attempts to do what his younger self thought he'd already done—leave his old world behind. In Amiens, Eddy realizes that the values and mores of his hated village are not universal and can be rejected. But he can't quite fit in with his middle-class peers. Enter Elena—a wealthy, bourgeois student whom Eddy admires from afar, then befriends, then begins to emulate. The first part of Change is titled after her, and is addressed to Eddy's father: "When I met Elena I became attached to a new way of life, to the codes of a new social class… because all of that allowed me to take revenge on my childhood, to give me power over you, over my past, over poverty, over the insults, and in imitating this life I was gaining access to a world that had always intimidated you."

The beginning of his transformation with (or into) Elena is exciting and shameful and painful. He changes his accent; she helps him dress better and eat properly with a fork and knife. After learning of the dangers of smoking around children, Eddy returns to his home full of righteous anger and starts a fight with his mother: "I shouted that she was a bad mother, unable to raise children… Because of you I'm going to fucking die, I said, you made me breathe in your smoke for my whole childhood, do you have any idea what you did to me, you ruined me." They trade blows until she hits him, both of them yelling and crying. "After that clash I realized I couldn't go back to the village on weekends," he writes. "I'd become someone else."

The Eddy of Change is motivated solely by his desire to avenge his past—to show everyone who bullied him and underestimated him and trapped him that he is better than they are. It is only a matter of time, then, before this almost pathological desire leads him to abandon his life in Amiens for something greater. After a few years, he meets Parisian intellectuals and decides he wants to be like them instead—Elena, who once seemed so cosmopolitan and rarified, now seems provincial in comparison. More importantly, Amiens is too close to home, and "being in Amiens meant remaining a prisoner of my childhood." In the same way he became bourgeois by imitating Elena, he decides to become an intellectual by imitating his new friends—reading books, doing scholarship, writing his own work. "If I really wanted to avenge the child I'd been, like Didier I had to go to Paris and do what he'd done," he reasons. "Hadn't I promised myself that one day I'd be famous and important, hadn't I wanted the boys at school to see what I'd become and pay for what they'd done to me, to regret their acts and suffer from the gap between their lives and mine?" His new intellectualism also coincides with accepting his homosexuality and officially coming out—his Parisian friends are gay, and Édouard sees in them a viable and exciting lifestyle.

Édouard the narrator sees everything he does as a definitive break, a border crossing between his past and his future. When he has sex with a man for the first time, he thinks, "I've crossed a line." When he's accepted to the École Normale, he thinks, "I'm saved." When a wealthy Parisian gives him his phone number for a date, he thinks, "I've made it." As a refrain, it's almost comical—to see the young Édouard say to himself, every few pages, "Okay, now I really can't go back," only to find himself still caught up in his past—although the comic can easily turn tragic, as in one scene in Paris in which Édouard, low on money, has to scrub the floors of rich people's mansions: how far has he really come? As he fraternizes with the uber-wealthy, and feels disgust at their lifestyle, he comes to desire revenge not only against the people of his past, but also against the entire system of power and wealth that oppressed them. What does he want, deep down, he wonders, as he considers his social ascent. "Did I want to become bourgeois? to get rich? to become an intellectual? to be famous? to be rid of the threat of poverty for good?" He finally writes his first novel, but it is, of course, not the escape he thinks it will be.

Change is more straightforward than The End of Eddy, and perhaps a less impressive feat. In Louis's previous works, other people, especially Eddy's family, are allowed to be deep, complex characters—victims as well as villains. In Change, by contrast, everyone conforms to Édouard's relatively linear narrative; if people are presented as complex, it is not because they are shown acting in interesting ways but because Édouard explicitly analyzes the conflicting forces acting on or through them. Elements of Louis's previous works that seemed to me more traditional—characters with ambiguous motivations and feelings; tension about what will happen next (even as we know how the story will end eventually); room for surprise—are missing. This is perhaps especially true for the character of Édouard himself, who is presumably a charismatic guy—Everyone loves him! People pay for his rent and dental surgeries and international flights! Total physical and intellectual transformations aren't cheap—but appears charmless and monomaniacal on the page.

And yet I loved Change and its monomaniacal narrator: his rigorous honesty, his physical inability to lie to himself about what he wants or what he will accept; the way he honors his life by working hard for his future self. His story is familiar, even if his circumstances are extreme. Feeling shame and spite at our past selves; the way excitement at the future turns the present into the living past and the future into the present; the desire to escape our past and start over completely, to live without ennui, to think "this is not enough for me" and move on, no matter how painful—these are universal experiences and desires, rendered on the page with seriousness and intelligence, in a story that is, like the stories of many great writers, equally aspirational and depressing.

Book reviewed by Chloe Pfeiffer

In addition to being a novelist, Édouard Louis, author of Change, is a scholar of the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. Louis's scholarly work has explicitly informed his novels, which are about the violence and indignity of poverty, the racism and homophobia of his working-class childhood, and the difficult act of moving between classes.

In addition to being a novelist, Édouard Louis, author of Change, is a scholar of the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. Louis's scholarly work has explicitly informed his novels, which are about the violence and indignity of poverty, the racism and homophobia of his working-class childhood, and the difficult act of moving between classes.

In 1979, Bourdieu published Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (1979), which Louis called, in conversation with Stephen Patrick Bell for the LA Review of Books, "probably the most important book about social classes since the works of Karl Marx. For sociologists all around the world, it completely flipped the script on the old analysis of what social classes are."

Distinction was based on data collected in France in the 1960s and 1970s and is about the relationship between social classes, status groups, and cultural capital. Unlike theorists who came before him, Bourdieu's theory of class is that it is not entirely economic, but also symbolic: made up of social practices. One of his most famous but also most debated theories is habitus, which is defined as a socially constituted system of dispositions that orient the "thoughts, perceptions, expressions, and actions" of a social class. So class, for Bourdieu, is not immutable or purely economic (say, the bourgeoisie versus the proletariat), but also related to lifestyle and cultural values. The social capital attached to one's class is a key aspect of his sociological landscape: having social status over someone else allows one to have "power over" them, even if it is not economic power. We can see Bourdieu's ideas animating Change, as Louis imitates the lifestyles of the latest class he'd like to join, and in successfully moving up, he gains power over the people from his past.

Bourdieu's ideas especially shaped Louis's consideration of the violence of his childhood. The real subject of his debut novel The End of Eddy, Louis said in an interview with The Paris Review, "is how people like the ones in my village suffer from exclusion, domination, poverty… these circumstances produce brutality through what Pierre Bourdieu called the principle of the conservation of violence. When you're subjected to endless violence, in every situation, every moment of your life, you end up reproducing it against others, in other situations, by other means."

In Acts of Resistance, Bourdieu wrote: "You cannot cheat with the law of the conservation of violence: all violence is paid for, and for example, the structural violence exerted by the financial markets, in the form of layoffs, loss of security, etc. is matched sooner or later in the form of suicides, crime and delinquency, drug addiction, alcoholism, a whole host of minor and major everyday acts of violence."

One of the instruments of this daily violence, Louis added, is the "cult of masculinity," which dominates the life of his autobiographical character Eddy as a gay and effeminate youth in The End of Eddy. Referencing Bourdieu in conversation with Bell, Louis said that "we take everything from the working class: we take money from them, we take access to culture, we take access to so many things from them, and the only thing that is left for working-class people is their body, and not for so long. And so, Bourdieu says we should not be surprised if there is an important ideology of what is the body, what is strength, what is physical domination, and maybe, by extension, masculine domination, homophobia and everything, the cult of the strong body."

Reading Louis's novels through this sociological—and inherently political—lens is a fascinating and educational exercise.

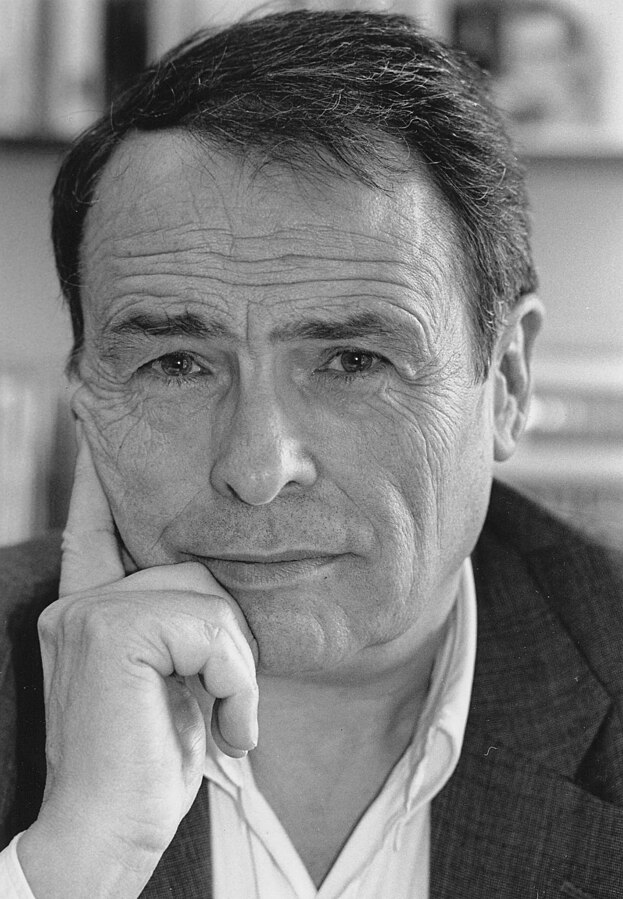

Pierre Bourdieu, 1996

Photo by Bernard Lambert (CC BY-SA 4.0)

by Ben H. Winters

What if time could be taken from us—the minutes, the hours, the years of our lives, extracted like organs taken for transplant? What would it mean for the world? And what would it do to the person from whom it's taken?

Grace Berney is a mid-level bureaucrat in the Food and Drug Administration, a woman who once brimmed with purpose but somehow turned into a middle-aged single mom with a dull government job and a melancholy sense that life has passed her by. Until the night a strange photo comes across her desk, of a young woman in a hospital bed who has been subjected to a mysterious procedure. Against orders and against common sense, Grace sets out to bring the girl to safety, and finds herself risking her job, her future, and her life on whether she can find the missing girl before an obsessive and violent mercenary who's also looking. Big Time is a fast-paced thriller and a metaphysical mystery about the very nature of our lives.

Big Time, the latest offering from prolific novelist and screenwriter Ben H. Winters, is as philosophical as it is electrifying to read. Set in the near future, the novel follows the interwoven stories of three Maryland women. Allie has just escaped an attempted kidnapping. Awakening in the hospital with fragmented memories and a strange device implanted in her chest, she is adamant that someone is still after her, though she doesn't know why. Desiree is Allie's would-be assailant. She was hired to bring the target to her client and is determined to see the job through no matter the cost. Grace balances caring for her teenage child and aging mother with her work at the Center for Devices and Radiological Health. She is brought in after hours to look into the unusual model of portacath (see Beyond the Book) found inside Allie.

Grace's investigation sparks the unravelling of a dangerous conspiracy built on the notion that time may be a physical entity held within all of us. If it can be isolated and harvested, time could be taken from one person and implanted into another, essentially shortening someone's lifespan in order to extend that of someone else. She soon realizes that Allie has been an unwitting test subject in a morally corrupt experiment, knowledge that will put both women at great risk.

Despite grappling with grand concepts like the ethics of contemporary science and the nature of time itself, the novel never gets bogged down in its own philosophical wonderings. Instead, these ideas form the framework for a speculative, corporate thriller that favors intrigue and a focus on its characters over a desire to present solid answers to any of the questions it poses about the potential future relationship between time, technology and humanity.

That is not to say, however, that the book does not have any worthwhile commentary to offer on the matter. There is, in fact, a significant thread on the human cost of scientific experimentation in the pursuit of medical breakthroughs. It asks us to consider the morality of pushing for advancement simply because something is theoretically possible, despite considerable risk, as well as the danger of exploitation if something like time were to become a commodity that vulnerable people could be pressured into selling.

Though the novel shifts regularly between the three women's third-person perspectives, each character remains distinctly drawn, ensuring readers can always keep track of who they are following at any given moment. When the story opens, we find Allie in a vulnerable, distressed state, but we watch her increasingly take back control as she resolves to find out why she has been targeted. Desiree, meanwhile, remains cold and ruthlessly determined to see her job through. She sits in stark contrast with Grace's strong moral compass and maternal instinct, which compel her to try to help Allie. Social commentary and further depth emerge around the experiences of Grace's teenager, who is non-binary and uses they/them pronouns. Though their gender non-conforming identity is discussed, it is done so in a seamless, breezy way, never being the focus of any conflict or drama. Normalized, integrated representation of a variety of identities is important, and it is handled here with due sensitivity.

Although the climax comes and goes a bit too quickly, Big Time consistently remains as compelling to read as it is thought-provoking, meaning it should appeal to lovers of sci-fi thrillers and metaphysical musings alike.

Book reviewed by Callum McLaughlin

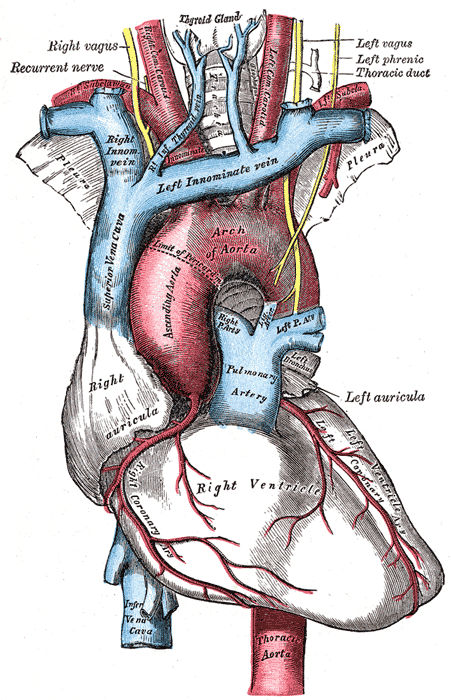

A portacath is a medical device used to assist with the treatment of ongoing conditions, most commonly cancer. It is composed of two key parts: the portal, which is a small chamber usually made of silicon that is placed just beneath the skin on a patient's chest; and the catheter, which is a flexible, hollow tube that is threaded into the superior vena cava—the vein that leads to the heart. The device's name is a portmanteau of these two parts.

A portacath is a medical device used to assist with the treatment of ongoing conditions, most commonly cancer. It is composed of two key parts: the portal, which is a small chamber usually made of silicon that is placed just beneath the skin on a patient's chest; and the catheter, which is a flexible, hollow tube that is threaded into the superior vena cava—the vein that leads to the heart. The device's name is a portmanteau of these two parts.

The purpose of a portacath is to provide quick access when administering repeated doses of intravenous (IV) fluid over a prolonged period of time. After numbing the skin over the port, a special needle called a Huber needle can be painlessly inserted directly into the chamber, allowing fluids to be given with ease. This means that in addition to administering chemotherapy, antibiotics and transfusions, portacaths can be used to extract blood samples, making them useful for people whose conditions will require ongoing blood tests as part of their treatment plan.

With a single portacath able to last between 2 and 6 years depending on the model and to withstand around 2000 punctures, most people who opt to have one fitted do so because they eliminate the need for repeated needle injections during long-term treatment. Finding and injecting veins can be both uncomfortable for the patient and time-consuming for medical professionals, while a portacath provides direct access to the patient's bloodstream whenever required.

In most cases, a small bump can be seen or felt where the port sits beneath the skin, but aside from this, it is generally considered a discreet solution that minimizes pain and discomfort in the long run. Other benefits of a portacath include lower infection rates and fewer care requirements when compared to other IV treatment methods.

Most people are able to have a portacath fitted under local anesthetic, meaning they can remain conscious throughout the procedure and return home within a matter of hours. Once treatment has been completed, the device is removed in much the same way.

In Ben H. Winters' novel, Big Time, one of the protagonists is found to have been fitted with an unusual model of portacath. Digging into its origin begins to unravel a tangled conspiracy that puts her and others in danger. Fortunately, most people's real-world experiences with a portacath are far less dramatic, and many finds it helps streamline their treatment.

Diagram of the heart showing position of the superior vena cava, courtesy of Henry Gray, Anatomy of the Human Body (1918).

by Stephanie Dray

Raised on tales of her revolutionary ancestors, Frances Perkins arrives in New York City at the turn of the century, armed with her trusty parasol and an unyielding determination to make a difference.

When she's not working with children in the crowded tenements in Hell's Kitchen, Frances throws herself into the social scene in Greenwich Village, befriending an eclectic group of politicians, artists, and activists, including the millionaire socialite Mary Harriman Rumsey, the flirtatious budding author Sinclair Lewis, and the brilliant but troubled reformer Paul Wilson, with whom she falls deeply in love.

But when Frances meets a young lawyer named Franklin Delano Roosevelt at a tea dance, sparks fly in all the wrong directions. She thinks he's a rich, arrogant dilettante who gets by on a handsome face and a famous name. He thinks she's a priggish bluestocking and insufferable do-gooder. Neither knows it yet, but over the next twenty years, they will form a historic partnership that will carry them both to the White House.

Frances is destined to rise in a political world dominated by men, facing down the Great Depression as FDR's most trusted lieutenant—even as she struggles to balance the demands of a public career with marriage and motherhood. And when vicious political attacks mount and personal tragedies threaten to derail her ambitions, she must decide what she's willing to do—and what she's willing to sacrifice—to save a nation.

Our First Impressions reviewers enjoyed reading about Frances Perkins, Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Secretary of Labor, in Stephanie Dray's novel Becoming Madam Secretary; out of 33 reviewers, 32 gave the book four or five stars.

What it's about:

The prologue begins with a scene in FDR's office in 1933 where he is asking Frances Perkins to be his Secretary of Labor. For reasons we learn later, she has already decided she will not accept the appointment. She lays out what she would do if she had the position, assuming that her agenda is so radical that he won't agree to it. To her amazement, he does. How could she say no? Chapter One takes us back in time to the summer of 1909, when Frances is getting a master's degree in economics. Upon graduation, she begins a career of fighting for workers' rights. She observes the tragic Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, which makes her an unstoppable force for safety in the workplace. Her successes attract the attention of New York Governor Al Smith and Theodore Roosevelt, as well as FDR.

The author delves into Perkins' personal life, a happy marriage that gradually disintegrates due to her husband's mental illness, which seems to be genetically transmitted to their daughter as well. It was for this reason that she was reluctant to take the position offered by FDR. But she did, and brought about legislation that even today affects every citizen of the US. Without Frances Perkins, there is some doubt that we would have ever had Social Security, minimum wage, unemployment insurance, child labor laws, and so many other safety net programs (Jim T).

Readers loved learning more about Frances Perkins' work and were impressed with all she was able to accomplish at a very misogynist time in history.

But the real story here is how she had to endure hatred, lies, death threats, scorn in the press, and sabotage by other members of the Cabinet; yet she maintained her dignity, pressing forward to get the programs she knew were needed by the American people. This is a book about history, but more importantly an inspiring story about courage and persistence in the face of seemingly impassable barriers (Jim T). Her struggles to overcome the horrors of unfair, cruel, and unsafe work environments, poverty and her own personal struggles at home are a testament to her strength and character so very well portrayed in the book (Miss Liz).

In addition to her professional accomplishments, readers found Dray's depictions of Perkins' personal life compelling.

Her support of her husband and daughter during their struggles with mental illness and her deep friendships attest to her strength of character. The author, Stephanie Dray, did an excellent job bringing Frances Perkins to light in this book (Ellen H). Dray also portrays Perkins' struggles, so pertinent to many working women, to juggle her commitment to being a loving, available mother to her daughter throughout their lives with her commitment to her equally demanding and fulfilling work life (Dianne S).

Becoming Madam Secretary has what many see as the markers of a successful work of historical fiction.

The job of writing historical fiction about a larger-than-life character like Ms. Perkins and all the important people she had to push, cajole, and convince, requires not only extensive research but also the creativity to try to discern and write what plausibly could have been her thoughts and her conversations. Stephanie Dray does a masterful job of all of the above. As she says in her Author's Note, "Novelists can go where historians rightly fear to tread." (Jim T). What a great book! I'm embarrassed to say I knew nothing of Frances Perkins nor her incredible achievements. A fiction book that sends the reader searching for more information must be a great book and this is one of them. I continue to be astonished that a book about the woman deeply involved in FDR's New Deal and the architect of Social Security could be such a page-turner! (Jeanne W).

While some found the writing style to be less than desirable…

The book is often repetitive and provides overly exhaustive detail, especially regarding her relationships with Paul and Ramsey. I often found I skipped whole pages to avoid some details (Dianne S). At times her characters felt rather flat, and the tone seemed superficial. The novel was a bit long, but there was so much territory to cover. This was an easy read, interesting and informative (Ruthie A).

...others found it exceptional.

Her writing pace matches the intense drama and passion of Perkins and like-minded women who sought out justice and fair labor practices. Because of her ability to tell a good story while revealing significant facts about women in history, the reader comes away from each chapter breathless for the next one (Ricki A).

And many felt it would be a good choice for a book group discussion.

The influence of Frances Perkins continues to this day. Book groups will find much to discuss about Ms. Perkins' personal life, professional life, and the balance between them (Shawna L). Dray, true to her previous books, has woven an interesting dialogue covering some very important parts of the history of our nation. A book worth reading for your personal illumination as well as a book destined for book clubs and the many different directions the conversations can flow (Carole A). I have suggested to the members of my book club we read Becoming Madam Secretary and look forward to a great discussion with other thoughtful women on a subject that has benefited us in our own life endeavors (Ricki A).

Book reviewed by BookBrowse First Impression Reviewers

Becoming Madam Secretary by Stephanie Dray narrates the life of Frances Perkins, Secretary of Labor under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the first woman to serve in the US Cabinet. Perkins was a tireless supporter of workers' rights and is credited with drafting and lobbying support for some of the most critical parts of the New Deal.

Becoming Madam Secretary by Stephanie Dray narrates the life of Frances Perkins, Secretary of Labor under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the first woman to serve in the US Cabinet. Perkins was a tireless supporter of workers' rights and is credited with drafting and lobbying support for some of the most critical parts of the New Deal.

Frances Perkins was born in Boston in 1880 and grew up in Worcester, Massachusetts. She attended college at Mount Holyoke where she studied economic history and was inspired by Jacob Riis's account of life in New York City's slums, How the Other Half Lives. She toured factories and interviewed workers to get a sense of the conditions and the issues that mattered to them. From Mount Holyoke, Perkins moved on to Wharton School of Finance and Commerce at University of Pennsylvania, and then Columbia University, where she earned a master's degree in economics and sociology.

After acquiring her degree in 1910, Perkins worked with social reformer Florence Kelley as the Secretary of the New York Consumers' League, advocating for the abolition of child labor and a shorter work week. She also became involved in the movement for women's suffrage at this time, taking part in marches and giving speeches on street corners to drum up support. In 1911, Perkins witnessed the chaos of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, a horrifying event that radicalized her on the need for worker protections and rights.

Perkins married Paul Wilson, an economist with the New York Bureau of Municipal Research, in 1913, and the couple had a daughter shortly thereafter. Perkins began working for the New York State Industrial Commission in 1918 at the behest of Governor Al Smith, and when Franklin Delano Roosevelt succeeded Smith as governor, he made Perkins Industrial Commissioner of New York. After the stock market crash in 1929, Roosevelt appointed Perkins to head up a committee on unemployment.

When Roosevelt was elected president in 1932, he asked Perkins to be his Secretary of Labor; a scene Dray writes into the prologue of her novel to capture the reader's attention. Perkins served from 1933-1945, which remains the longest term served by a Secretary of Labor. Her achievements include the Wagner Act, which protects workers' rights to form unions and engage in union activities such as collective bargaining and striking, and the Fair Labor Standards Act, which created a minimum wage, established guaranteed time-and-a-half for overtime, and eliminated "oppressive child labor." Perhaps most significantly, Perkins chaired the Committee on Economic Security in 1934, which drafted the set of policies that would become the Social Security Act (SSA). The SSA established a pension fund for retirees as well as funds to assist low-income elders.

Perkins went on to travel as a delegate to the International Labor Organization Conference in Paris in 1945, and to work in the Civil Service Commission under President Truman. She died in 1965 at age 85.

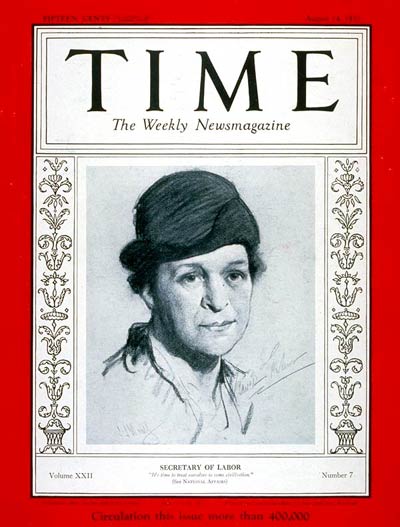

Frances Perkins on the cover of Time, 1933, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

by Vanessa Le

Nhika is a bloodcarver. A coldhearted, ruthless being who can alter human biology with just a touch.

In the harsh, industrial city of Theumas, she is seen not as a healer as she was meant to, but a monster that kills for pleasure. And in the city's criminal underbelly, the rarest of monsters are traded for gold. When Nhika is finally caught by the infamous Butchers, she's auctioned off to the highest bidder—a mysterious girl garbed in white. But this strange buyer doesn't want to use Nhika as an assassin or a trophy piece. She intends to use Nhika's bloodcarving to heal the last person who saw her father's killer.

As Nhika delves into the investigation amid Theumas's wealthiest and most powerful, all signs point to Ven Kochin, an alluring yet entitled physician's aide intent on casting her out of his opulent world. But despite his relentless attempts to push her away, something inexplicable draws Nhika to him. When she discovers Kochin is not who he claims to be, Nhika must face a greater, more terrifying evil, turning her quest for justice into a fight for her life.

Her only chance to survive lies in a terrible choice—become the dreaded monster the city fears, or risk destroying herself and the future of her kind.

The city-state of Theumas is a gleaming metropolis of advanced technology and innovation where the use of automatons is commonplace and modern medicine is seemingly developing at a rapid rate. However, alongside the opulent wealth and industrialists exists another Theumas of impoverished boroughs, black market trading, and violent crime. In this indigent part of the city, 18-year-old Nhika scrapes a living under the radar as a homeopathic healer, called upon in secret when even Theumas' highly advanced medicine fails to cure the ill and dying.

But Nhika's on-the-surface talent for homeopathic remedies is a disguise for her true ability. For she is what is known in Theumas as a bloodcarver: a magical being who can alter human biology with just a touch, for good or bad; someone who can heal the sick or wound fatally if they so wish. Bloodcarvers are not native to Theumas. They are people from the island of Yarong, which was conquered and colonized by Theumas' warring neighbor Daltanny, and they were rounded up, experimented on, and ultimately believed to have disappeared completely. They are creatures of legend, feared as blood-hungry vampiric monsters, but belief in them endures in Theumas, where, the author tells us, "people worshipped the scientific method over the gods of old and ignorance followed faithfully in the shadow of achievement." She continues, "They claimed that innovation conquered all, but Nhika knew best that fear and superstition were immortal." The daughter of Yarongese refugees, Nhika has inherited her abilities as a bloodcarver from her mother and grandmother, and believes herself to be the last of her kind. When she is discovered, betrayed, and captured by a gang known as the Butchers, she is sold to the highest bidder with far-reaching and devastating consequences.

The worldbuilding of The Last Bloodcarver is vivid and potent, with picturesque, evocative descriptions contrasting the wealthy milieu of Theumas' elite with the gritty, often gruesome world of its underclass. Adding depth and resonance is the portrayal of racial differences and prejudices established within this secondary world, with Nhika described as having "golden-brown skin, dark irises, and hair the color of coffee rather than ink," which sets her apart from the pale-skinned, black-haired people of Theumas, and often causes her to be regarded with suspicion and hostility. Nhika is a sympathetic and engaging heroine, tough and resourceful owing to her circumstances, and also intensely lonely and vulnerable, believing that there is no one else like her left alive, and carrying with her the grief and guilt of being unable to cure her dying mother despite her magical abilities.

The supporting characters are also well-drawn, nuanced, at times mysterious, and convincingly unpredictable as we see them through Nhika's eyes. The detailed anatomical descriptions of Nhika's blood magic surging through human bodies are lucid and eloquent, combining beautiful phrasing with intricate medical and biological knowledge, lending the magic a sense of heightened realism. It is emphasized that in Yarongese culture bloodcarvers "call themselves heartsooths," and that Nhika's grandmother has taught her that the ethos of heartsoothing, like medicine's Hippocratic oath of "First, do no harm," is to help people, not hurt them: "That is the core of heartsoothing. Not to harm. To heal." Heartsooths see their abilities as both magical and scientific, requiring study and practice, just like conventional medical surgery. Magic and medicine intertwine throughout the story to poetic and powerful effect, and this interconnection is key to the mystery at the heart of the plot.

There are scenes of extreme violence that are on occasion quite graphic, particularly towards the beginning during Nhika's capture and incarceration by the Butchers. These scenes do, however, establish in no uncertain terms just how dark and perilous Theumas can be beneath its shiny veneer of modernity and progress, how high the stakes really are, and the nature of the terrible dangers Nhika faces. As the first in a duology, with several unexpected twists and a tantalizing cliffhanger, The Last Bloodcarver is an excellent debut that bodes well for the second book.

Book reviewed by Jo-Anne Blanco

In Vanessa Le's debut YA novel The Last Bloodcarver, her heroine, Nhika, is the titular protagonist: a person with the power to alter anatomy with a single touch, able to travel through a body's bloodstream, and cure it, wound it, or end its life altogether. Bloodcarvers can also feed on blood and proteins from other humans and animals to heal themselves if they are ill or injured. Nhika inherits this blood magic from her family. Le is a Vietnamese American author who, according to her bio, "loves reading and writing stories about the Asian diasporic experience and high-concept magic systems." Her first novel, described as "a Vietnamese-inspired dark fantasy" incorporates both of these subjects into a steampunk secondary world. Le is far from the only YA author to include blood magic in a fantasy novel in recent years. The following list looks at books by other Asian American authors who incorporate this feature into their worldbuilding.

In Vanessa Le's debut YA novel The Last Bloodcarver, her heroine, Nhika, is the titular protagonist: a person with the power to alter anatomy with a single touch, able to travel through a body's bloodstream, and cure it, wound it, or end its life altogether. Bloodcarvers can also feed on blood and proteins from other humans and animals to heal themselves if they are ill or injured. Nhika inherits this blood magic from her family. Le is a Vietnamese American author who, according to her bio, "loves reading and writing stories about the Asian diasporic experience and high-concept magic systems." Her first novel, described as "a Vietnamese-inspired dark fantasy" incorporates both of these subjects into a steampunk secondary world. Le is far from the only YA author to include blood magic in a fantasy novel in recent years. The following list looks at books by other Asian American authors who incorporate this feature into their worldbuilding.

Xiwei Lu, who publishes under the name Marie Lu, was born in China and grew up in the US. In 2014, she published the first novel in a YA trilogy titled The Young Elites. Here, blood magic is not an inherited ability, but a consequence of a blood fever that affected children. The fever gave them psi powers, making them the objects of suspicion and prejudice. Lu's protagonist and main narrator, Adelina, is, unlike Nhika, an anti-heroine similar to Anakin Skywalker/Darth Vader in Star Wars, and the trilogy's subsequent books, The Rose Society (2015) and The Midnight Star (2016), chronicle her tragic downfall.

South Korean-born, Minnesota-raised Kendare Blake published the first book in her Three Dark Crowns series in 2016. It revolves around a set of female triplets, each with an inherited power from their bloodline: Katharine, who is immune to all poisons; Mirabella, who commands the elements; and Arsinoe, who wields power over nature. While all three are heirs to the crown, only one can become queen and the sisters eventually have to fight each other to the death for the throne. In addition to Three Dark Crowns and the following novels One Dark Throne (2017), Two Dark Reigns (2018), and Five Dark Fates (2019), Blake published two prequel novellas, The Young Queens (2017) and The Oracle Queen (2018), which expand on the blood magic and origins of the three sisters.

In her Shadow Players trilogy — For a Muse of Fire (2018), A Kingdom for a Stage (2019), and On This Unworthy Scaffold (2021), Heidi Heilig creates a powerful heroine in Jetta, who can see the dead and bind their souls to her shadow-player family's puppets with her blood. Hawaiian-born Heilig is Chinese American and her series is inspired by Southeast Asian cultures and French colonialism. Similarly, in the 2021 YA novel Jade Fire Gold, Singaporean American author June C.L. Tan addresses colonialism, writing, "History is never written by its victims," and creating a world in which the characters are uncertain about their country's true past. In this novel, inspired by Chinese folklore and wuxia (martial arts) TV shows, Tan's heroine, Ahn, also struggles with her blood magic, which gives her the ability to steal people's souls.

Perhaps the closest to The Last Bloodcarver's Nhika in blood magic is the protagonist of Amélie Wen Zhao's Blood Heir trilogy. Zhao was born in Paris, raised in Beijing, and currently resides in New York, and her multicultural upbringing inspired the themes of her books. Her heroine, Ana, is the Crown Princess of the Cyrilian Empire and an Affinite, a magical person with the ability to control the world around them. Ana is similar to Nhika in that she is a Blood Affinite, one who can control and manipulate blood, even as it courses through a person's body. Like Nhika, Ana is feared, has to hide her power, and is forced to go on the run. Over the course of the three books, Blood Heir (2019), Red Tigress (2021), and Crimson Reign (2022), Ana eventually loses her blood magic and must discover who she is without it.

In addition to the aforementioned Asian American authors are many others, such as Lori M. Lee, with her Hmong-inspired Shamanborn series, and Lena Jeong, with her Korean-inspired Sacred Bone trilogy. All of these, along with Vanessa Le, bring their own perspectives to tales of dark fantasy and blood magic.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.